Iranian Combinatorics Olympiad 2024

I competed in this contest with dantoh and tqbfjotld.

You can find problems for the qualification round here and the problems for the final round here.

The problems were fun to solve, but the general organization. I’m still not satisfied with how problem 2 and 5 of the qualification round was handled, along with the timer issue for the qualification round.

So the first issue was the timer started 20 mins late for the qualification round. I guess it was fine because they sent the english statement in the telegram channel 4 mins into the contest, and it was fair. Even though the timer suggested that the contest would end 20 mins later, it ended on time. Luckily, we had saved our answers periodically. But we missed out on 2 yolo marks on the qualification (2 and 15). And our yolo for 15 would have been correct. There was no apologies from the organizers about this…

And if you check the scoreboard for the advanced and free division, you will see that the top teams all got P5 from qualification wrong. So everyone kind of knew that something was wrong with Jury solution, but they only annouced it on telegram 2.5hours before the finals instead of a few minutes after the contest ended. Did no one check the scoreboard?

I also have issues with P2 from qualification. The statement suggests to me that the answer for any such arrangement of points is the same. So dantoh decided to try a regular hexagon which gave him $3$ configurations. I sent another set of points (triangle in triangle) which I thought had only $3$ configurations but dantoh managed to find $4$. Then dantoh managed to destroy the problem more by finding another set of points with $5$ configurations. So the question is totally wrong! But the organizers don’t want to admit it after writing about it in CodeForces.

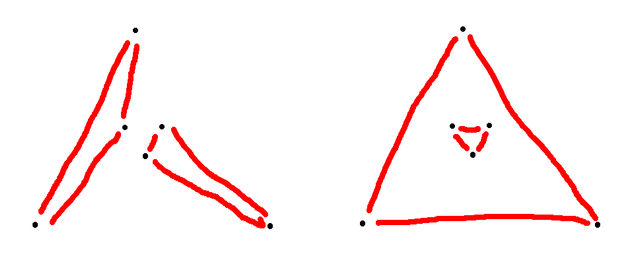

Anyways, here are the construction for $3$, $4$ and $5$ different configurations.

$3$ configurations: regular hexagon

$4$ configurations: triangle in triangle

$5$ configurations: regular pentagon with point inside

What we think the answers are for qualification round:

- 550

- ?

- 16536900

- 101

- 192

- 123

- 48

- 180

- 104857

- 2

- 1

- 6

- 51

- 199

- 39

Below are writeups of some problems in qualification round (the harder ones).

3

The answer is $\binom{2n}{n}^2$

Let a upper left set be a set $S$ such that if $(x,y) \in S$, then $(x-1,y) \in S$ and $(x,y-1) \in S$.

Similarly let a bottom right set be a set $T$ such that if $(x,y) \in T$, then $(x+1,y) \in T$ or $(x,y+1) \in T$.

We claim that the grids form a bijection with all pairs of sets $(S,T)$. $S$ contains the positions of all $1$ and $2$s, and $T$ contains all the $2$s and $4$s. It is not too hard to prove that this is a bijection.

But of course, I wasn’t smart enough to notice this so I wrote code…

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

#define int long long

#define rep(x,start,end) for(int x=(start)-((start)>(end));x!=(end)-((start)>(end));((start)<(end)?x++:x--))

int arr[8][9][9];

signed main(){

int n=8;

rep(x,0,n+1) rep(y,x,n+1){

if (x==y) arr[0][x][y]=1;

else arr[0][x][y]=2;

}

rep(i,0,n-1) rep(x,0,n+1) rep(y,x,n+1) rep(x2,0,n+1) rep(y2,x2,n+1) if (x2<=x && y2<=y){

if (x2==y2 || x<y2) arr[i+1][x2][y2]+=arr[i][x][y];

else arr[i+1][x2][y2]+=2*arr[i][x][y];

}

int ans=0;

rep(x,0,n+1) rep(y,0,n+1) ans+=arr[n-1][x][y];

cout<<ans<<endl;

}

4

Morteza can guarantee that he can make $101$ moves. For the first $99$ moves, form a tree.

Then bicolor the tree such that alternate vertices have different colors. On the $100$-th move, when Matin picks vertex $x$, Moteza just picked vertex $y$ with the same color as vertex $x$ and connects them. The only time when this is not possible is if the tree is a star with $x$ as the center. But then Matin is not allowed to pick vertex $x$, since $x$ would be full in this case. So the graph has no even cycles after the $100$-th move.

Then Matin can make the moves so that Morteza is forced to form an even cycle on the $101$-th move.

For the first $99$ moves, Matin picks isolated vertices so that Morteza is forced to make a tree. Then in the next $2$ moves, Matin will pick any leaf $r$ twice. Suppose Morteza picks $a$ and $b$ to connect to connect with $r$. Let $g$ be the LCA of $a$ and $b$ when $r$ is the root. Then there are the following $3$ cycles:

- $r \to a \hookrightarrow r$ using $1+d(a,r)$ moves

- $r \to b \hookrightarrow r$ using $1+d(b,r)$ moves

- $r \to a \hookrightarrow g \hookrightarrow b \to r$ using $1+d(a,g)+d(b,g)+1=2+d(a,r)+d(b,r)-2d(g,r)$ moves

Under modulo $2$, we have that $a+1$, $b+1$ and $a+b$ are all odd. This is absurd. Their sum is even. So the tree contains an even cycle after the $101$-th move.

7

We can prove the answer is not $49$ by analyzing the row sums. That is $R_i = A_{i,1} \oplus A_{i,2} \oplus \ldots \oplus A_{i,7}$.

Then notice that any operation flips three consecutive elements of $R$. If we define $C$, we get a similar thing. Anyways, the thing to notice is that this is a vector space of dimension $7$ but we only have $5$ possible operations, so the kernel is at least $2$ for both $R$ and $C$. In particular, the vector of all $1$s is not inside, so it is impossible that all cells are $1$.

I didn’t have a smart way to construct $48$. I couldn’t do it by hand so I just wrote a code to do it.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

#define int long long

#define rep(x,start,end) for(int x=(start)-((start)>(end));x!=(end)-((start)>(end));((start)<(end)?x++:x--))

int basis[49];

void add(int i){

rep(x,0,49) if (i&(1LL<<x)){

if (basis[x]) i^=basis[x];

else{

basis[x]=i;

return;

}

}

}

signed main(){

rep(x,0,7) rep(y,0,7){

rep(d1,-1,2) if (d1) rep(d2,-1,2) if (d2) if (0<=x+d1*2 && x+d1*2<7 && 0<=y+d2*2 && y+d2*2<7){

int bm=0;

rep(z,0,3){

bm|=1LL<<((x+d1*z)*7+y);

bm|=1LL<<(x*7+(y+d2*z));

}

add(bm);

}

}

rep(x,49,0){

rep(y,0,x) if (basis[y]&(1LL<<x)) basis[y]^=basis[x];

}

rep(x,0,49) cout<<bitset<49>(basis[x])<<endl;

int bruh=0;

rep(x,0,49) bruh^=basis[x];

cout<<bitset<49>(bruh)<<endl;

}

Interestingly, the kernel has dimension $4$, which means that our condition about the row and column sums are also sufficient.

Because suppose that for a $n \times m$, we have filled all cells except $(n,m-2)$, $(n,m-1)$, $(n,m)$ and $(n-1,m)$. Then there is a unique way to fill these cells that satisfy the conditions that $R$ and $C$ are generated by flipping $3$ consecutive elements.

Also, we can show that for $n\geq 3$, the dimensions the span for a $3 \times n$ grid is $4(n-2)-(n-3)=3n-5$.

First, note that the piece

XOOO

XOOO

XXXO

is the sum of all the below pieces

XXXO OXXX OOOX

XOOO OOOX OOOX

XOOO OOOX OXXX

Therefore, $3n-5$ pieces span the vector space. We will show that they are all independent.

If $n>3$, all the pieces that touch the first column are

XXX XXX OOX

XOO OOX OOX

XOO OOX XXX

We can determine the correspondence by first the middle row, to determine whether the first L is flipped. Then the top and bottom row the second and third L.

When we get to $n=3$, all the Ls are independant.

abc

def

ghi

There is a unique cell that will change $a \oplus b$ and $f \oplus i$. It is the L below

XOO

XOO

XXX

In the same way, by comparing appropriate pairs of values, we can figure out whether each L was flipped.

So the dimension is exactly $3n-5$.

While for $4 \times 4$ grids (and therefore bigger grids as well), the kernel is has dimension $4$.

We will demonstrate it. . means that the tile has a fixed value and ? means that we don’t care about the value of the tile. Our goal is to change ? to . and make as many . as possible. We will do it in the reverse direction.

....

....

...?

.???

.... OOOO

...? OOOX

...? OOOX

.??? OXXX

.... OOOO OOOO

...? OXXX OXXX

.?.? OXOO OOOX

.??? OXOO OOOX

.... OOOO

.?.? OXOO

.?.? OXOO

.??? OXXX

.... OOOO

.??? OXXX

.?.? OXOO

.??? OXOO

.... OOOO

.??? OXXX

.?.? OXOO

.??? OXOO

.... OOXO OXXX OOOX OXOO OOOO OOOO OOOO

.??? OOXO OOOX OOOX OXOO XOOO OOXO XXXO

.??? XXXO OOOX OXXX OXXX XOOO OOXO OOXO

.??? OOOO OOOO OOOO OOOO XXXO XXXO OOXO

trivial parts ommitted

11

The strat for this seems to be write brute force and don’t think lol! The statement asks that we consider isomorphisms under cyclic rotation which evidently trolled alot of people.

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

#define int long long

#define rep(x,start,end) for(int x=(start)-((start)>(end));x!=(end)-((start)>(end));((start)<(end)?x++:x--))

signed main(){

rep(bm,0,1<<10){

bool ok=true;

rep(i,0,10){

bool can=false;

for (auto a:vector<int>({-1,1})) for (auto b:vector<int>({-1,1})){

if (((bm>>((i+a+10)%10))&1)==0 && ((bm>>((i+a+b+10)%10))&1)==1) can=true;

}

if (!can) ok=false;

}

if (ok) cout<<bitset<10>(bm)<<endl;

}

}

It outputs $10$ different strings, which are all rotations of 1100100100, so the answer is $1$.

15

Let $c$ be the unique center of the tree. That is the unique vertex where the maximum distance to any other vertex is $50$.

Let $S$ be the set of subtrees whose depth is $49$ and $T$ be the set of subtrees whose depth is $48$.

Firstly, we show that the answer is at least $\mid S \mid -1$. To show lower bound, let the operation be to just remove the edge, the lower bound will not be higher than the original statement. Obviously, we need to cut at least one edge from all but one of the $\mid S \mid$ subtrees.

Since $\lfloor \frac{2024-1}{50} \rfloor = 40$, the answer is at least $39$.

Now, to prove the answer is at most $39$.

Case $1$: $T = \varnothing$

Let the roots of the subtrees in $S$ be $s_1,s_2,\ldots,s_k$. Then for $s_2,s_3,\ldots,s_k$, delete edge $(c,s_i)$ and add edge $(s_1,s_i)$. We used $\mid S\mid-1 \leq 39$ operations.

Case $2$: $T \neq \varnothing$

Let the roots of the subtrees in $S$ be $s_1,s_2,\ldots,s_k$. Then for all vertices $v$ whose depth is exactly $48$ and is a descendant of one of $s_2,s_3,\ldots,s_k$, delete $(p_v,v)$ and add $(s_1,v)$.

Now, the number of such vertex $v$ is at most $\lfloor \frac{2024}{49} \rfloor-2 = 39$, the reason we can subtract $2$ is because there is at least $1$ such vertex $v$ in the subtree of $s_1$ and any vertex of $T$, it is isn’t empty.

Therefore, in this case, we used $\leq 39$ operations again.

The final round went ok… at the last hour of the contest, we had solved 1,2,3,5, and had lower bound construction for 4, upper bound construction for 6 and upper bound construction for 7. I was abit pissed because we got marked down for 1, even though I see no error with the proof. Maybe it is ugly to MO peope or something

Me and tqbfjotld decided to work on 4, seeing the number of solves. I told my idea to him and he was convined, so we were writing different parts of the proof in parrallel, since the details were quite involved. But alas, 17 mins before the end of the contest, I realized that my proof was wrong, we just wasted an entire hour….

Anyways, we realized we couldn’t salvage the proof for 4, so we just submitted the $ans \geq 3n -8$. For 7, we didn’t have any idea how to prove either so we just submitted $k \leq 1$.

For 6, I suddenly realized how to solve it with 10 minutes left. I asked dantoh for his partially written solution for 6 and quickly appended proof of lower bound. I left out a lot of details and calculations because we were out of time and I submitted it 1 minute before the contest ended. Miraculously, they awarded the proof full score (even though 1 was marked down…).

Below are the solutions we submitted. You can judge whether 1 should be marked down while 6 has perfect score.

Also, problem 5 is quite interesting to me. If you have the restriction that you want an independent set, the construction for $3^{n-1}$ is very easy. Just take all the sequences who sum is divisible by $3$. But after we relax the condition to allow each vertex to have at most $1$ neighbour, we managed to only add $1$ more vertex into the set… Surely this can’t be the upper bound right? It’s too cursed. But I’m too lazy to investigate further.

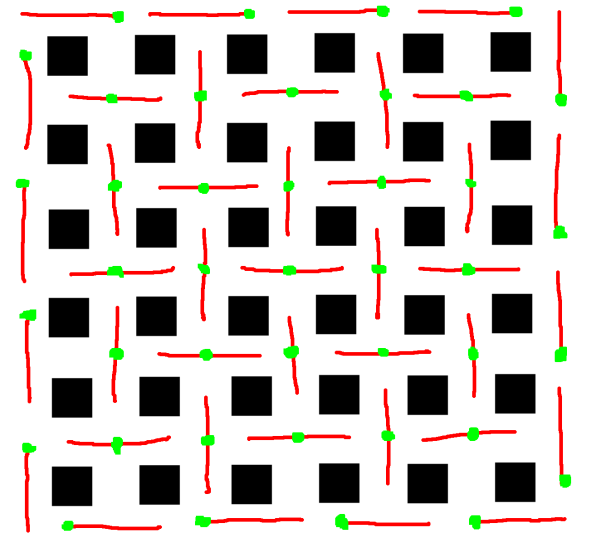

1

Below is a construction using $41$ tiles (in red lines). We have chosen $41$ green points such that there is no way to place a tile on the grid without touching a green point. One can manually check that for three consecutive horizontal or vertical tiles, there is at least one green point.

2

We split into cases of $n$ is even and $n$ is odd.

Firstly, we demonstrate a sequence of swapping steps in exactly $n$ moves. (part b)

If $n$ is even, the sequence of moves $(s,t)$ is $(1,n),(2,n-1),(1,n),\ldots,(1,n)$. That is we do $(1,n)$ on odd moves and $(2,n-1)$ on even moves.

If $n$ is odd, the sequence of moves $(s,t)$ is $(1,n-1), (2,n), (1,n),\ldots,(2,n)$. That is we do $(1,n-1)$ on odd moves and $(2,n)$ on even moves.

In both cases, we will prove that the element initially in index $k$ ends up in index $n+1-k$.

It is easy to see that if $k$ is odd, the path of the element will be $k \to k+1 \to k+2 \to \ldots \to n -1 \to n \to n \to n-1 \to \ldots \to n-k+1$.

Similar,y if $k$ is even, the path of the element will be $k \to k-1 \to k-2 \to \ldots \to 2 \to 1 \to 1 \to 2 \to \ldots \to n-k+1$.

Now, we prove that there is no sequence of swapping steps using $n-1$ moves. (part a)

The inversion count of the permutation is defined as the number of pairs $(i,j)$ such that $i<j$ and $\pi_i>\pi_j$. The in inversion count of the initial and final permutation is $\frac{(n-1)n}{2}$ and $0$ respectively.

A single swap will clearly decrease the inversion count by at most $1$.

If $n$ is odd, each swapping step will perform at most $\frac{n-1}{2}$ swaps, so we require at least $n$ swapping steps to decrease the inversion count by $\frac{(n-1)n}{2}$.

If $n$ is even, each swapping step will perform at most $\frac{n}{2}$ swaps. However, this only shows that we require at least $n-1$ swapping steps to decrease the inversion count by $\frac{n(n-1)}{2}$. However, notice that the only move that performs exactly $\frac{n}{2}$ swaps is $(s,t)=(1,n)$. If we perform two of such moves consecutively, the swapping steps would cancel each other out. Therefore, if $n \geq 4$, we need to perform at least one move that only does at most $\frac{n}{2}-1$ swaps. Therefore, we require at least $n$ swapping steps in this case too.

3

First, we show that the minimum $k$ is at least 6. We choose $A_1, A_2, A_3 \ldots A_{10}$ to be the $10$ different distinct subsets of size 3 of the set $\{1,2,3,4,5\}$. We choose $A_{11}, A_{12}, A_{13} \ldots A_{20}$ to be the $10$ different distinct subsets of size 3 of the set $\{6,7,8,9,10\}$. Suppose the covering subset has less than $3$ elements in $\{1,2,3,4,5\}$, then there exists a subset in $A_1, A_2, A_3 \ldots A_{10}$ that is not covered. Similarly, suppose the covering subset has less than $3$ elements in $\{6,7,8,9,10\}$, then there exists a subset in $A_{11}, A_{12}, A_{13} \ldots A_{20}$ that is not covered. Hence, a minimum of $3+3=6$ elements are required in $S$

Next, we show that there always exists a subset of size $6$ that is a covering subset We define $f(x)$ to be the number of $i$ where $S \bigcap A_i = \emptyset$ and $x \in A_i$ To choose the elements of the subset $S$, we repeatedly choose $x \in X$ where $x\notin S$ and $f(x)\geq f(y)$ for any $y\in X$, and add $x$ to $S$. Let $n_j$ be the number of $i$ where $S \bigcap A_i = \emptyset$ after $j$ elements have been added to $S$. Due to pigeonhole principle, $n_{j+1} \leq n_j-\lceil{\frac{3n_j}{10-j}}\rceil$. Hence, $n_{j+1}\leq n_j \cdot \frac{7-j}{10-j}$ $n_6 \leq n_0 \cdot \frac{7}{10}\cdot \frac{6}{9}\cdot \frac{5}{8}\cdot \frac{4}{7}\cdot \frac{3}{6}\cdot \frac{2}{5} = \frac{n_0}{30} = \frac{2}{3}$ Since $n_6$ must be a non-negative integer, $n_6=0$, hence there exists a subset of size $6$ that will cover all $A_i$

4

We assume the graph is simple. That is, it does not contain any self-loops or multiedges.

We know that for any planar graph, with $n$ vertices and $m$ edges, we have $m \leq 3n-6$.

Let the maximum number of cycles of length $3$ be $c$. We will show that $c \leq m-2$, so that $c \leq 3n-8$.

Firstly, let us show that it is possible to construct a graph with $3n-8$ cycles of length $3$.

Number the vertices from $1$ to $n$. Add the following vertices:

- $(1,2)$

- $(1,x)$ for $3 \leq x \leq n$

- $(2,x)$ for $3 \leq x \leq n$

- $(x,x+1)$ for $3 \leq x \leq n-1$

The $3n-8$ cycles of length $3$ are given by:

- $n-2$ cycles of the form $(1,2,x)$ for $3 \leq x \leq n$

- $n-3$ cycles of the form $(1,x,x+1)$ for $3 \leq x \leq n-1$

- $n-3$ cycles of the form $(1,x,x+1)$ for $3 \leq x \leq n-1$

It remains to show that $c \leq m-2$.

[Omitted is my fakesolve. I tried to see if it would fool the markers. It didn’t.]

5

5a

All arithmetic in this solution are taken under modulo $n$.

Lemma $1$: Consider the set of vertices $\{x,x+1,x+2,x+3\}$. We claim that $S$ should contain at most $2$ elements from this set.

Proof: Suppose that $S$ contains $3$ elements from this set, which we call $a < b < c$. We have $b-a \leq 2$ and $c-b \leq 2$, so that $b$ is adjacent to both $a$ and $c$, which is not allowed. $\blacksquare$

If $n=1$, $S=\{1\}$ and $f(G)=1$.

If $n=2$, $S=\{1,2\}$ and $f(G)=2$.

If $n=3$, $S=\{1,2\}$ and $f(G)=2$. We cannot have $f(G)=3$ or else $S=\{1,2,3\}$, violating lemma 1.

Otherwise now suppose that $n \geq 4$.

Let $C(l,r)$ denote the number of vertices in $l,l+1,\ldots,r$ that is contained in $S$.

By lemma $1$, $C(l,l+3 ) \leq 2$.

$4f(G) = C(0,3) + C(1,4) + \ldots + C(n-2,1) + C(n-1,2) \leq 2n$. Therefore, $f(G) \leq \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$.

For $n = 0,1,3 \pmod 4$, we can find a set $S$ such that $\mid S\mid = \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$ so that it hits our upper bound on $f(G)$.

- $n = 0 \pmod 4$, $S = \{0,1,4,5,\ldots,n-4,n-3\}$, $\mid S\mid = \frac{n}{2} = \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$.

- $n = 1 \pmod 4$, $S = \{0,1,4,5,\ldots,n-5,n-4\}$, $\mid S\mid = \frac{n-1}{2} = \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$.

- $n = 3 \pmod 4$, $S = \{0,1,4,5,\ldots,n-7,n-6,n-3\}$, $\mid S\mid = \frac{n-1}{2} = \lfloor \frac{n}{2} \rfloor$.

Now, consider that $n \geq 6$ and $n = 2 \pmod 4$. We claim that $f(G) = \frac{n}{2}-1$.

Now, to obtain $f(G) = \frac{n}{2}$, the formula $4f(G) = C(0,3) + C(1,4) + \ldots + C(n-1,2) \leq 2n$ must be tight, so that $C(l,l+3)=2$ for all $l$. Since $C(x,x+3)=C(x+1,x+4)$, we have $x \in S \leftrightarrow x+4 \in S$. Since $n=2 \pmod 4$, we also have $x \in S \leftrightarrow x+4 \in S \leftrightarrow \ldots \leftrightarrow x-2 \in S \leftrightarrow x+2 \in S$ so that $x \in S \leftrightarrow x+2 \in S$.

Now, the only way that $x \in S \leftrightarrow x+2 \in S$ and $C(l,l+3)=2$ for all $l$ is for $S=\{0,2,4,\ldots,n-2\}$ or $S=\{1,3,\ldots,n-1\}$. But for we can observe both sets violate the condition of each element being adjacent to at most one other.

Therefore, $f(G) < \frac{n}{2}$ in this case. We can hit this upper bound with $S = \{0,1,4,5,\ldots,n-6,n-5\}$, $\mid S\mid = \frac{n}{2}-1$

In summary, we have proved that:

- If $n=1$, $f(G)=1$

- If $n=2$, $f(G)=2$

- If $n=3$, $f(G)=2$

- If $n\geq 4$ and $n=0 \pmod 4$, $f(G) = \frac{n}{2}$

- If $n\geq 4$ and $n=1 \pmod 4$, $f(G) = \frac{n-1}{2}$

- If $n\geq 4$ and $n=2 \pmod 4$, $f(G) = \frac{n}{2}-1$

- If $n\geq 4$ and $n=3 \pmod 4$, $f(G) = \frac{n-1}{2}$

5b

For each $n$ will construct a set $S_n$ of size exactly $3^{n-1}+1$ such that for all sequences, there is exactly one adjacent element.

Our base case is $S_1 = \{(1),(2)\}$.

For $n \geq 1$, will construction $S_{n+1}$ using $S_n$. Let $T_n$ be sequences of length $n$ such that their sum is divisible by $3$. Then $\mid T_n\mid = 3^{n-1}$ because for each sequence of length $n-1$, there is a unique number to add to it to obtain a sequence of length $n$ whose sum is divisible by $3$.

For each element in $S_n$, append $0$ and call it set $A$.

For each element in $T_n$, append $1$ and call it set $B$.

For each element in $T_n$, append $2$ and call it set $C$.

We claim that $S_{n+1} = A \cup B \cup C$ works. It should be clear that all $3$ sets are pairwise disjoint since their last element differs.

When $n=1$, we have $A=\{(1,0),(2,0)\}$, $B=\{(0,1)\}$ and $C=\{(0,2)\}$. So $S_2 = \{(1,0),(2,0),(0,1),(0,2)\}$

When $n=2$, we have $A=\{(1,0,0),(2,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,2,0)\}$, $B=\{(0,0,1),(1,2,1),(2,1,1)\}$ and $C=\{(0,0,2),(1,2,2),(2,1,2)\}$. So $S_3 = \{(1,0,0),(2,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,2,0),(0,0,1),(1,2,1),(2,1,1),(0,0,2),(1,2,2),(2,1,2)\}$

Lemma $1$: $\mid S_n\mid = 3^{n-1}+1$.

Proof: For $n=1$, $3^{1-1}+1 = 2$.

For $n \geq 1$, assume the statement is true for $S_n$.

$\mid S_{n+1}\mid = \mid S_n\mid + 2 \cdot 3^{n-1} = 3^{n-1} + 1 + 2 \cdot 3^{n-1} = 3^n +1$

By induction, the statement is true for all $n$ $\blacksquare$

Lemma $2$: For all sequences in $S_n$, their sum is not divisible by $3$.

Proof: For $n=1$, it is clearly true.

For $n \geq 1$, assume that the statement is true for $S_n$.

We will show that this implies that the property for $A$, $B$ and $C$ of $S_{n+1}$ all holds. Sequences in $A$ have the same residue as their corresponding element in $S_n$, which we know is not divisble by $3$ by our induction hypothesis. Sequences in $B$ and $C$ have residue $1$ and $2$ modulo $3$ by our construction. For all sequences in $S_{n+1}$, their sum is not divisible by $3$.

By induction, the statement is true for all $n$ $\blacksquare$

Lemma $3$: For all sequences in $S_n$, there is exactly one adjacent element.

Proof: For $n=1$, it is clearly true

For $n \geq 1$, assume that the statement is true for $S_n$.

Consider sets $A$, $B$ and $C$ in $S_{n+1}$. If $a \in A$ and $b \in B$, then we claim that they are not adjacent. This is because $a$ and $b$ differ on their last element, which is $0$ and $1$ respectively. So if they are adjacent, then the first $n$ elements of $a$ and $b$ must be same. However, the sum of the first $n$ elements of $a$ and $b$ are respectively non-zero by lemma 2 and zero by our construction of $B$. The same argument applies to show that for all $a \in A$ and $c \in C$, they are not adjacent.

Now, for each element $a \in A$, the only possible elements it can be adjacent to are other elements in $A$. If $a_1, a_2 \in A$ are adjacent in $A$, it must also be adjacent in $S_n$ by our construction. So all element in $A$ are adjacent to exactly one element.

For two different elements $b_1, b_2 \in B$, they have the same sum under modulo $3$. But if they differ in exactly one position, then their sum modulo $3$ would be different. Therefore, they are not adjacent. The same argument applies to show that for two different elements $c_1,c_2 \in C$, they are not adjacent.

Finally, for each element $b \in B$, the only possible element it can be adjacent to are elements in $C$. If $c \in C$ is adjacent to $b$, the first $n$ elements of $b$ and $c$ must match. Clearly, there is at most one such $c$. By our construction that $c$ exists in $C$. The same argument applies to show that for each element $c \in C$, there is exactly one element adjacent to it in $B$.

By induction, the statement is true for all $n$ $\blacksquare$

Therefore, we have constructed a family of sets where $S_n$ has size exactly $3^{n-1}+1$ and for all sequences, there is exactly one adjacent element. Therefore, $f(G) \geq 3^{n-1}+1 > 3^{n-1}$.

6

Claim: $f(n) = \lfloor\frac{n(n+1)}{6}\rfloor$

Base cases:

$n = 1: no valid moves, $f(n) = 0$

$n = 2: \{1, 2\} \rightarrow \{0, 1\}, f(n) = 1$

$n = 3: \{1, 2, 3\} \rightarrow \{1, 0, 1\}, f(n) = 2$

Claim: $f(n) = f(n-3) + n-1$

Proof:

For $1 \leq x \leq n-1$ let $T_x$ be the time that we perform the operation on index $x$ and $x+1$. If we do not perform the operation, then $T_x =\infty$. We will let the non-infinite $T_x$ be all distinct so that this is well-defined. For convinience, define $T_{0} = T_{n} = \infty$.

Consider the largest index $1 \leq x \leq n-1$ such that $T_{x-1} > T_x < T_{x+1}$.

Then we will have $T_x<T_{x+1}<\ldots<T_{n-1}<T_{n} = \infty$. Suppose instead that there is a $y>x$ such that $T_{y-1} > T_y$. Then there must be a $x<x’$ such that $T_{x’-1} > T_x’ < T_{x’+1}$ since $T_n = \infty$. So $T_x<T_{x+1}<\ldots<T_{n-1}<T_{n} = \infty$ clearly holds.

If $x=n-2$, consider last 3 elements of $\{1, 2, … n\}$.

$\{n-2, n-1, n\} \rightarrow \{0, 1, n\} \rightarrow \{0, 0, n-1\}$ with cost $n-1$.

Now we have $\{1, 2, …, n-3, 0, 0, n-1\}$ which has cost $f(n-3)$ so that $f(n) \geq f(n-3) + n -1$.

But if we have $x \neq n-2$, we can show that this will result in a lower value for $f(n)$.

For example, if $x=n-1$, we have $f(n) = f(n-2) + n-1$ instead.

If $x=n-3$, we have $f(n) = f(n-4) + (n-4) + (1) + (n-2)$ instead.

and so on, which is worse than when $x=n-2$.

Thus $f(n) = f(n-3) + n-1$.

Induction: assume $f(x) = \lfloor\frac{(x)(x+1)}{6}\rfloor$ is true for every $x <= k$.

Then $f(k+1) = f(k-2) + k = \lfloor\frac{(k-2)(k-1)}{6}\rfloor + k = \lfloor\frac{k^2 - 3k + 2}{6}\rfloor + k = \lfloor\frac{k^2 + 3k + 2}{6}\rfloor = \lfloor\frac{(k+1)(k+2)}{6}\rfloor$

Thus $f(k+1)$ is true.

7

We show a construction which has only 1 empty consecutive triplet.

Choose any points $P_1, P_2, P_3$.

for point $P_k$, choose any point within the triangle $P_{k-3}P_{k-2}P_{k-1}$.

Now we will only have $P_{98}P_{99}P_{100}$ as an empty consecutive triplet.

Thus $k \leq 1$.

We think $k=0$ is not possible… so $k=1$.