Some Musings on Informatics Olympiad Training

The links in this blog post is split into two types. In-line links like this are links that are not important while links like $[x]$ are important and you might want to read a few of them if you have time.

Some time ago, I was made aware of the NUS module ALS1010 - Learning to Learn Better which led me into kind of a rabbithole of researching on how to learn better. Over the years, many high profile competitive programmers have written their ideas on how to train for competitive programming. See $[1]$, $[2]$, $[3]$, $[4]$, $[5]$ along with the age-old quote “solve more problems”. So here is my version.

Since, I was going to be doing informatics olympiad training stuff after finishing National Service, I guess it is a good time to write down what I think about this topic. This is the advice that I wish I could give to my younger self. I don’t think it is a big secret that I dedicated at least the last 3 years of my high school life for the sake for informatics olympiad. My younger self would probably be happy if to be able to read the info that I am writing in this post (and I guess also that he managed to get 2 IOI golds).

There will be some advice on how to do competitive programming in this blog. But this advice will be bullshit if you don’t actually practice. This is especially true in the language learning community where many people are too caught up in some optimal way for learning language that they spend more time optimizing their language learning than actually learning a language. So the first step that I must mention at the start is to actually spend time practicing.

Why did I do Informatics Olympiad?

Now, during semester 2 of 2018, I overcommited like crazy. If my memory served me right I was simultaneously in:

- Informatics Olympiad Training (CS3234)

- Physics Olympiad Training (PC2231)

- Math Olympiad Training (MA2231V)

- SIMO Junior Team

Everyone likes to think that they are superman and that they can handle this workload. No, you are not. I did not learn anything from doing this and was just completely wasting my time. I can confidently say I bombed everything (except MA2231V) just because I didn’t have enough time. Do not expect to make it into national team for 2 different subjects.

But the merit of going through this was that I could better make the choice between physics, maths and informatics olympiad. Obviously, I chose informatics olympiad.

As I recall, these are my reasons to pursue informatics olympiad:

- I was really good at guessing stuff and Proof by AC

- Programming was cool, writing a few lines of code that allows a computer to do some insane number crunching in 1s that a human could never do in it’s lifetime felt like black magic to me

- There are 1023981202382839 people in both Math and Physics olympiads. The most likely way to win a ticket to an international olympiad was informatics

- In Maths Olympiad, there are so many people who have already had a headstart. It wasn’t so unusual to see the primary schooler at SMO Junior. It seemed utterly impossible for me to catch up to them

- Informatics Olympiad has very little prerequisite knowledge, you can quickly jump to the “interesting” parts of the olympiad. Seriously, you cover basically all foundational things in 1 year (or in 1 month in dec course). Meanwhile look at Maths or Physics Olympiad. They are much older olympiads so the accumulated knowledge is so much that you are stuck learning content the entire time

If you ask me now, why I still do competitive programming. Of course, I will give very different reasons than when I started. But it is not like these reasons are very deep as well. I recall that I had an interview with the principals of NUS High for some scholarship. I got asked some question like “You have spent a lot of time on Informatics Olympiad. What do you like about it?”. I didn’t really have much to say. I just said “It’s fun.” Then the vice-principal told me after the interview that my answer was not acceptable and that it is what he would expect a primary school student to say, but I am not a primary school student.

Honestly, I think that what the vice-principal told me was complete bullshit. Of course, you should come out with a “politically correct” response for such interviews. But deep down, I know that the reasons I still do competitive programming is:

- I am good at it

- The problems in competitive programming are very intellectually stimulating to solve, you really wouldn’t get that experience elsewhere, other than maybe pure maths

- It is fun to compete and interact (including irl) with other competitive programmers

Recently, I also had to write my UCAS personal statement about why I want to study mathematics, which forced me to think about why I want to study mathematics. In contrast to other STEM subjects in which their study can be immediately be justified from their utility. One must one to face that mathematics and informatics olympiad is useless. I don’t have any noble reason to spend my time on “solving maths problems with computer” and that’s fine. I won’t give an entire argument about why I think it is justified to waste your life on something useless as Hardy has already done it very aptly in $[6]$.

And if your only reason to do informatics olympiad is because you think you can become good at it. That’s fine as well. That’s basically my motivation when I started. And to quote Hardy, “… perhaps five or even ten percent of men can do something rather well. It is a tiny minority who can do something really well, and the number of men who can do two things well is negligible. If a man has any genuine talent he should be ready to make almost any sacrifice in order to cultivate it to the full.” And Hardy himself did not have any deep reason to Mathematics in his younger days as well, as he writes “I do not remember having felt, as a boy, any passion for mathematics, and such notions as I may have had of the career of a mathematician were far from noble. I thought of mathematics in terms of examinations and scholarships: I wanted to beat other boys, and this seemed to be the way in which I could do so most decisively.”

But sincerely, I hope that eventually the problems themselves to be interesting of their own right to be able to justify why you find informatics olympiad fun.

Here are some problems with very little prerequisite knowledge that I hope that you can enjoy without any prerequisite knowledge (do not open the editorials, it really is worth it to solve these problems yourself):

What Makes Someone Better at Informatics Olympiad?

There are 3 main things to learn in Informatics Olympiad.

- Learning to code

- Learning classic algorithms

- Learning problem solving

The main thing that separates people in Informatics Olympiad is really point 3. I’m sure that many people are better coders than me, using fancy code completers and IDEs while I am basically using notepad + terminal with print statements to debug. The set of classic algorithms that everyone needs is pretty much the same as well. There is a set syllabus for IOI and one can always google stuff in contest time. Um_nik famously wrote a blog about all the algorithms he doesn’t know. So really, the only thing that can actually separate people at the top is how good they are at problem solving. This is known as ad-hoc. In Chinese it is known as 人类智慧.

Actually, you may not realize this yet, but all the classic algorithms you spend so much time learning when you just start informatics are kind of useless when you go to higher levels. I don’t think I’ve ever written SPFA or Floyd-Warshall recently. It really is just attacking problems from first principles without using any classic algorithms. And if hard problems do require knowledge of classic algorithms, they are difficult not because they require knowledge of classical algorithms but because they require difficult and creative thinking.

Of course, you should not neglect the first two stages. A solid foundation of the stage $i$ is necessary to be good at stage $i+1$. It is just that mastery of writing code and of classic algorithms should only take a few years. Mastery of problem solving itself will never end. But note that it is not like you must completely master (in the Japanese sense) stage $i$ before you move onto stage $i+1$. It’s more like you should get decently competent at stage $i$ before going to stage $i+1$.

How to be Better at Problem Solving?

Solve more problems lol.

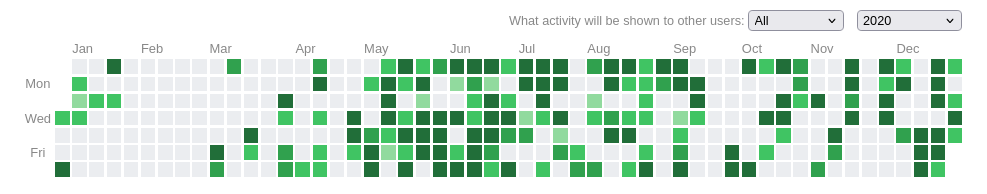

As a reference, this is how many problems I have solved:

- Codeforces: 2132

- Atcoder: 742

- Codebreaker: 835

- Other OJs: ???

I believe that I improved like crazy during the COVID lockdown period where I spammed Codeforces like crazy.

But what exactly are you learning from doing all these problems? See this Jeff Bezos decided not to become a physicist, where Yasantha solves a PDE that Bezos couldn’t solve because he saw it before. Essentially, you are going to build a gigantic database of problem solving techniques that will be your guide whenever you are tackling a new problem.

In $[7]$, Gowers also talks about combinatorics, which he describes as “problems that it is reasonable to attack more or less from first principles”, which honestly is quite similar to how I would describe the problems in competitive programming. But then if everything is done from first principles, what even allows the field as a whole to progress? To which Gowers say “However, it is not true that there is no structure at all to the subject. The reason it appears to many mathematicians as though combinatorics is just a miscellaneous collection of individual problems and results is that the organizing principles are less explicit. … The important ideas of combinatorics do not usually appear in the form of precisely stated theorems, but more often as general principles of wide applicability.”

As pointed out in $[8]$, we can think about problem solving as traversing a graph. People who are better at problem solving are just able to save time traversing their graph by making better heuristics. They have also been exposed to way more problems, which allows them to think of stuff that you will you never have thought of.

Sometimes, these problem techniques are written explicitly in folklore. Some examples I can think of on the top of my head are:

- Look for invariants

- If it is a bitwise problem, solving bit by bit usually works

- Think about doing queries offline

You can find alot more examples of these kinds of general problem solving tricks in $[9]$ and $[10]$.

But more often than not, these tricks are never written down explicitly, and it is even difficult for people to explain how their mind works, which makes this problem solving thing seem more mysterious than it actually is. Unfortunately, the only way for you to build your database of problem solving technique is to keep solving more problems.

But it is abit misleading to talk about only these as databases. Because it makes it seem that these tricks are all disconnected from each other. But we actually arrange these tricks as a heirachy as stated in $[11]$, which I encourage you to read. But briefly, if we image our knowledge as vertices. There are also connections between these knowledge. For example:

- If $X$ is a problem and $Y$ is a technique, there can be an edge that is “$X$ is solved using technique $Y$”

- If $X$ and $Y$ are both problems, there can be an edge that is “$X$ and $Y$ are quite related”

- If $X$ and $Y$ are both techniques, there can be an edge that is “$X$ is a more general version of $Y$”

It is very hard for anyone to teach you explictly all these relationships. You really have to get your hands dirty by solving a lot of problems and making these connections yourself.

The Need for Memorization

In the past, I was too prideful to do anything that has any semblance to memorizing. I thought that memorising anything was the ultimate evil in education and that biology was the ultimate evil subject.

But honestly, as I hope to have shown above, most of our knowledge is really from memorizing stuff. How do the top informatic olypmpiad participants build their insane knowledge databases of problems? They solving a lot of problems but in additional have a lot of the problems stored in their memory. Seriously, ask any serious contender for the IOI. They will probably be able to tell you all the IOI problems in the last 5 years. Ask any serious contender for the IMO. They will probably be able to tell you all the IMOSL problems in the last 5 years. We stop really stop being ashamed of memorizing.

For a while now, I wanted to learn Japanese, but I never took the leap because I was struggling so much on Chinese that I took O Level twice. You have to be insane to learn a language that loaned their writing system and half their vocabulary from Chinese. But I was bored during National Service, nothing to do, so I decided to just take the plunge and start learning Japanese. Many others who were learning Japanese would recommend Anki. I have been using Anki for a little over 6 months now and learnt 5k+ vocab cards at the moment. This isn’t clickbait. Anki is just that good.

What is Anki? It is just a simple flashcard app. Each card has a “front” and “back” side. You will only see the “front” side of the card and you need to recall the “back” side of the card. Then you will flip the card and check whether the back side matches. It also spaces out cards so that you will receive a card when Anki think that you almost forget it. You can find a guide to using Anki at $[12]$.

What should you add to Anki? Well, obviously Algorithms. Put the “front” side as like “Dijkstra’s Algorithm” and the “back” side as an explanation to Dijkstra’s Algorithm (or maybe a link to a website that explains it).

But how do we add undescriable techniques into Anki? Well, instead add the important problems that correspond to those tricks and make sure that whenever they appear, you are able to solve them. Note that it isn’t desirable for you to memorize exactly how to solve these problems but instead to resolve them. If you set up Anki properly, the same problem would appear with such a large frequency that ideally you forgot how to solve the problem by the time it gets to you.

Some problems that directly correspond to tricks in my mental database is:

- COCI poklon, doing queries offline

- NWERC Installing Apps, do greedy before doing DP

And generally, whenever you stumble across a problem whose solution is something you would never have thought of, you can add it into Anki. We don’t want to add every single problem into Anki or it will just be wasting your time. Just add the important ones.

As for how to add problems into Anki. For the “front” side of the card, you can either put a link to the problem statement or just write a formal statement. I prefer the latter. For the “back” side of the card, write a very brief solution, or even just put a link to an editorial.

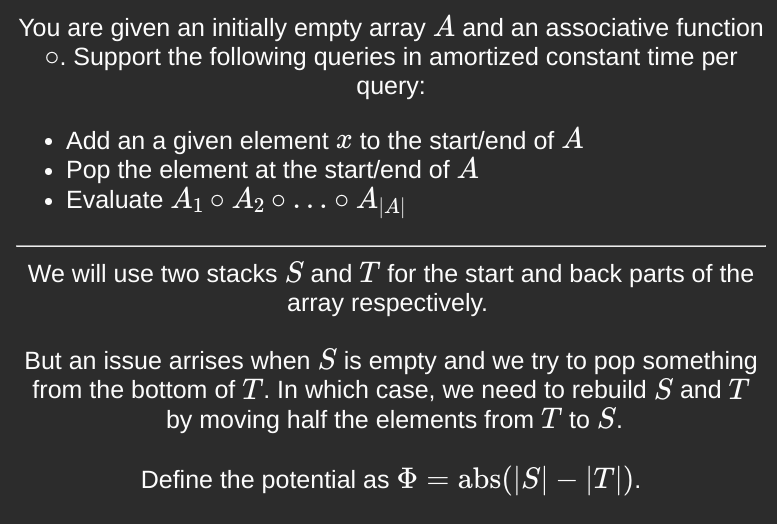

This is an example card from my Anki deck.

And well, if you really like Anki, you can use it for revising your schoolwork too I guess.

Note that here, I am not encouraging shallow memorizing, like you might need to do in biology, where you memorize all these different things as disjoint facts. The point of using Anki is to keep refreshing your memory about old problems so that your brain is more able to make connections with things that you have seen before, in hopes of putting these ideas into your deep memory with many connections. So maybe using “memorizing” here is abit misleading.

Pragmatic Advice for Practicing

Evan Chen has written about this for Math Olympiad in $[13]$. And more generally, Dahaene, a neuroscientist, has written about this from in $[14]$, which I really recommend reading part three.

As I said above, I practiced like crazy during COVID. How exactly did I practice? I picked a random 2400-rated problem on Codeforces. If I couldn’t solve it within a few hours and I didn’t want to continue working on the problem, I read editorial. That’s all. It’s not that deep. Just pick a problem that you cannot guarantee that you can solve, but that you know is also not impossible for you to solve. Rinse and repeat until you get better. Heuristically, Codeforces rating + 200 works.

Should you solve problems outside of IOI syllabus? Yes. There is honestly no harm in doing so and it only adds to your knowledge graph. It’s totally possible that in IOI you are inspired by FFT to come out with a solution. Because if you study it, you realize it is just another occurance of DnC. So it allows you to add another vertex as a child to the very general topic of DnC.

How long should you practice for? Just as long as you still find the motivation to practice. See Radewoosh’s take on $[3]$. Even in Evan Chen’s FAQ, he literally writes “I would often think about math in passing (while walking between classes, sitting on the bus, etc.)” and I really find this true for me. At the same time, don’t force yourself to practice if you don’t want to. Instead watch anime or play MLBB or whatever. I know Yoneda writes in $[2]$ that he sometimes does two $5$-hour contests back to back. But honestly, that is insanely overkill. Informatics Olympiad is a very mentally draining olympiad. Your coding time is actually your rest time where the mental strain is much lower. It is very unfeasible for most people to spend more than a few hours a day on problem solving itself. So don’t be too hard on yourself and give in to hustle culture. At the end of the day, you need to accept that humans are really unproductive creatures.

As Um_nik points out in $[4]$, there are 2 orthogonal parts of competitive programming skill. Solving hard problems, and solving problems fast. In olympiad style contests, there really isn’t any reason to specifically train how to solve problems fast. You don’t have to go out of your way to train your contest strategy for 3/5 problems and 5 hours format. Just don’t make any stupid strategy like only coding when AC.

As for contests, I know some people who also keep a journal of their contest time. I think this is a good idea. Maybe it is also a good idea to keep track of how you are spending time when solving a problem. As pointed out in $[5]$, maybe you will realize that a lot of time you spend “solving” a problem is really pretending to yourself that you are practicing.

After you solve a problem, you are still not done, you should also do some reflections about how you solved the problems. Polya talks about this in $[9]$. Terrence Tao talks about this in $[15]$. And in the case where you do end up reading the editorial, try to explain the solution in a way that is motivable to you, so that you are confident that you can rederive the solution if a similar problem comes to you again. The point of this reflection is to deeply modify your knowledge data and strength the connection between different parts of it.

Should you solve problems topically or solve random problems? My take is whenever you learn a new technique, solve a few problems that uses this techniques. This will add the problems into your knowledge graph along with the common applications of the technique. You should reflect on what properties these problems share that would motivate you to use this technique. Then this will prepare you for applying the technique when you encounter these problems in the wild.

Problem Setting

As mentioned earlier, Codeforces Raif Round 1 was the first contest that I set on Codeforces. I set C and E. The story of E is quite funny, it caused a chain reaction of so many things.

So in November 2018, there was a school training with a problem set named “DP or Greedy ??”. Inside, there was the problem Zabava, I think you can see the resemblance to CF1428E, only the constraints are different.

So what happened was that Zabava was meant to be solved with DP. But for some reason I decided to solve it with greedy in $O(K \log K)$ without proof and it worked. After the contest, the editorial was presented and this was meant to be solved with DP so I was really confused. I left this problem at the back of my head for quite a while.

Then later when there were talks about making a round for Codeforces, I remembered that Zabava existed and proposed my $O(K \log K)$ solution. This became “canonized” into Singapore training syllabus as “Diminishing Returns” (I prefer calling it Convex Convolution now, see mamamintaplusa) in Dec Course 2022 Greedy Notes Section 4.4. And even better, the “Diminishing Returns” trick appeared in IOI 2020 Tickets, where only me and Adriel (how does his brain work) solved it.

Already we see an obvious benefit of problem setting in that it create another item in my (and other Singaporeans) mental database of problem solving techniques. But the other benefit is that it also makes you into a better contestant in a less direct way. $[11]$ tries to talk about this in the section “Applying creativity to create new ideas and contexts”. Physcologically, it also breaks a mental barrier when you put yourself in the shoes of a problem author creating a problem. Problems in contest just feel abit more possible to solve when I know that another human has solved this problem before.

On Being Able to Prove Solutions

The story of CF1428E was nice and all, but there was a giant issue. I couldn’t prove my solution for it.

When I started informatics olympiad. I did not know how to prove anything. I thought that this would be fine, because the way informatics olympiad works actually rewards this kind of behaviour with “Proof by AC” kind of things. I knew already that I did not have any Math Olympiad training which my peers already had, so I thought I would be fine not proving anything.

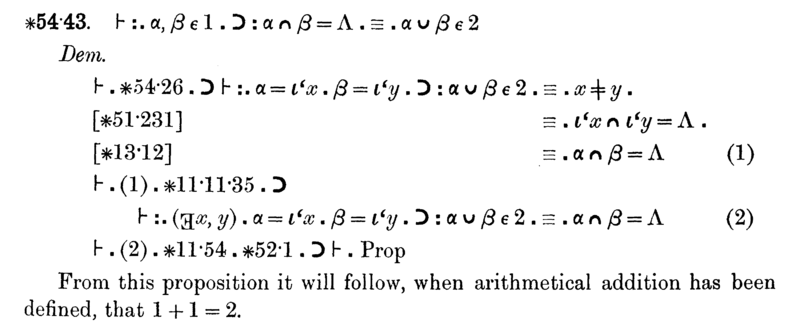

I had the misconception that the “real” work was in making observations and proving was some ugly contrived thing made by mathematicians was wanted to be formal as possible for no reason. School maths $[16]$ and the infamous 1+1=2 proof from Principia mathematica really made my perception of “real” proofs very wrong, thinking they had to be overly formal mumbo jumbo.

For the first year of my informatics olympiad training, I also never saw what an actual proof written by someone for informatics olympiad looked it. Sure, people talk about proofs like “exchange argument”, “stay-ahead” vaguely, but I have never seen what a “formal” version of these proofs were. If only someone had shown me what qualified as a “formal” proof years ago, I probably would have been more willing to learn how to write proofs.

Anyways, back to CF1428E. I recall that a few weeks before the contest, we still didn’t have a proof of the convexity of $f(n,k)$. Our coordinator told us to check it for all small values, which we already did. But it was so silly that no one had a proof. I remember sitting in a voice call with other people trying to solve it and having no clue. Then out of the blue, oolimry found a proof. I think this was when I realize how important proofs are. Like the “real” part of solving this problem was really in proving the convexity.

This applies the most to greedy problems. A lot of people just prove by AC. Yes, please do that during contest time. But after the contest, please do try and prove it. And I use the word “proof” use not to mean write down a formal mathematical proof but instead to convince yourself that the greedy algorithm is correct for example. Although when you are new, it might be really helpful to actually take out pen and paper and explicitly write down all proofs and maybe even ask someone to check it. Or just ask yourself for every line that you write, do you 100% believe in it? As Terrence Tao writes in $[17]$, “The point of rigour is not to destroy all intuition; instead, it should be used to destroy bad intuition while clarifying and elevating good intuition.”

At this point, it is also important to tell you that people also don’t do informatics olympiad by using rigour. We go intuition or vibes alot. I do commonly write brute force, simulation, whatever on small values to do pattern recognition and make conjectures (thank you OEIS). And if the conjecture seems correct, being able to articulate why it is correct may lead to you one step closer to a solution. But again, if you really cannot prove the conjecture and have already a working solution for the problem, just prove by AC already.

We Stand on the Shoulder of Giants

I have heard this quote being thrown around a lot. But I didn’t really understand the gravity of it until recently.

Take writing for example. To me and you, writing is the most obvious thing in the world.

But evidently, it took humans forever to come out with modern writing.

Writing was only independently invented 5 times (debatable) in the world:

- China, Chinese Characters

- Egypt, Hieroglyphs (English actually descended from broken telephone of Hieroglyphs if you didn’t know)

- Mesopotamia, Cuniform

- Mesoamerica, Mayan Script

- Indus River Valley, Indus Script

And all these writing systems are honestly very cursed. None of them are phonetic. Like really, no one figured out that words could be broken down into individual atomic sounds? The Japanese and Koreans evidently also did not realize how to write phonetically before the Chinese brought their writing system to them which was super ill-fitted to their language. While the Koreans managed to create hangul, the Japanese writing system is still remains cursed, not to mention others like the Yi Script with 1164 different syllabus.

But these people were by no means stupid. We need to appreciate how far human knowledge has come such that all English speakers today know intuitively that sound “cat” can be represented by the 3 sounds k + a + t. On that note, if you are struggling in learning how to read Chinese, please don’t give up because it’s “inefficient”. What other writing system allows one to read something written by a guy 2000 years ago?

Also, I would like to point out that we shouldn’t feel too proud that we are above these writing systems with our superior phonetic writing system. There have been 2 things that I learned in the past year that showed how little I actually know about how sound in language works.

- k and g may seem like completely different sounds, but they are kind of the “same” sound. In Japanese, ka and ga is か and が respectively, while ki and gi is き and ぎ respectively. Why is (ka,ga) more closely related than (ki,gi) in writing? Well it turns out they are only seperated by voiced and unvoiced distinction. Your tongue and mouth shape are the exact same. Japanese needs to mark voiced/unvoiced distinction like this beacuse of rendaku. This fact still doesn’t feel true in my brain.

- Another one related to this is g-k distinction. Let A = voiced velar plosive, B = unvoiced velar plosive, C = aspirated unvoiced plosive. Then the (g,k) pairs in English, Chinese and Japanese is (A,C),(B,C) and (A,B) respectively. The reason why Megan Thee Stallion sounds so obviously not Japanese in Mamushi is because she uses C instead of B for the t sound in “watashi wa star”. Also, I didn’t even realize that g was different in English and Chinese. In singlish, 打包 is usually written dabao by Chinese speakers but can be written as tapao as well (I have seen dapao once before). This is because we are too influenced by hanyupinyin, where the sound is B but it written as A, so we just accept that it is the same sound. By some magic, we are able to produce A and B correctly in the respective languages but we never stop associating it with the same sound in our head. It took me super long to unlearn this and I was so surprised to learn about this that I didn’t believe it at first. Again, this fact still doesn’t feel true in my brain.

There are a lot more things that civilizations didn’t think of that are obvious in hindsight. I’m sure you can come out with many examples.

I think I have made my case that in humankind, most innovations are really just someone taking the tiniest step, compared to what their ancestors have done before then.

In the past, there was a movement of “discovery-based learning”, where as describe in the section “The Failure of Discovery-Based Teaching” in $[14]$, where I quote “ How could we imagine that children would rediscover, in a few hours and without any external guidance, what humanity took centuries to discern?” and “And this is perhaps the worst effect of discovery learning: it leaves students under the illusion that they have mastered a certain topic, without ever giving them the means to access the deeper concepts of a discipline.”

The point of all of this is that you must be humble and willing to ask others for help when you don’t understand something. I have noticed that many people are too shy to ask question in informatics olympiad training out of fear of looking stupid. But guess what, informatics olympiad is hard. And I think generally the trainers would be more than happy to explain stuff with you if you don’t understand and are willing to learn.

Furthermore, this applies also to solving problems. If you think the problem is out of your reach, just be ok to give up and read the editorial. There is no shame in that. And even if you solved the problem, please do spend some time to read the editorial. Maybe the author did something better than you that you can learn? Maybe the author has a more motivable way of approaching the solution than you? Maybe the author’s code is cleaner? And why stop there. Maybe also ask your friends how they motivated their solutions if they solved it much faster than you? You are ultimately only impeding yourself if you want to cling onto your pride of solving every single problem without any help.

But on that point, I am not saying to give up on every problem and read the editorial after a few hours. There are some problems in which I indeed do try on and off for months at a time. There is no set rule for which problems I read editorial and which I keep at the back of my mind to try later. But it seems the heuristic I use is “Do I enjoy thinking about this problem?”.

Importance of Friends

For my first NOI selection, I finished 5th place in the school team selection. It turns out that evantually the people who ranked 1st-7th in that year’s NOI selection would evantually represent Singapore in the IOI. Maybe there are more but I forgot.

Coincidence? No. I argue that this happened because we were constantly competing against each other, which made NUS High into the crazy powerhouse it was. Just look at the Singapore IOI teams from 2020-2023. The number of NUS High people respectively are 6/8, 6/8, 4/4, 3/4.

For me, I believe I could only improve this much in the early stages because I was constantly competiting with these people. Whether in school trainings, codeforces, atcoder, IOI trainings, whatever. We were also very willing to share any random stuff that we learnt, which now I think about it, is quite weird since we were competiting against each other at the end of the day for IOI team spots since there were more than 4 of us in that group.

And friendly competition allows you to push yourself way beyond your limit. It is a well-documented thing in speedrunning that whenever someone manages to break a time limit barrier, that many more people in the weeks following will also break that record. That is, your mental block is removed. This seems to be called the Bannister Effect, named after Roger Bannister, the first guy to run a 4 minute mile.

When you see someone like tourist solve a problem you couldn’t solve. You don’t feel anything because yea, he is tourist after all. He is better than me. But when you see your friend being able to solve a problem that you couldn’t solve. You will know that:

- you have the ability to solve it, since you are about the same skill level as your friend

- you have to solve it to prove that you are at least as good as your friend

I personally experienced this on one and only time I ran sub-12 on IPPT . I saw my bunkmate in front of me and I was like “wtf” and run up to catch him. If it was a random guy, why would I care that he was faster than me?

With discord and all, you don’t even have to do this things with your schoolmates. Try to make friends with people in dec course who seem to be serious about informatics olympiad and train with them throughout the year. You will be surprised how much you can improve just by both parties forcing themselves to be better than another person.

Another reason to make friends in the informartics olympiad community is to do problem setting with your friends. You could do problem setting for codebreaker, but you can also aspire to do it for codeforces. Nepotism is very possible now that there are 2 codeforces Coordinators in Singapore, me and maomao90. If you want to reap the benefits of problem setting that I have previously mentioned, you could set it as a challenge with your friends to do that.

Importance of Sleep

Now on my last point. I don’t know why people in NUS High like to sleep very little. It is not uncommon for half the class to be sleeping and people seem to also like bragging about how little they sleep. I also fell into this trap. Tbh idk why.

Sleep is actually super important in learning. As Dehaene writes in $[14]$, “sleep is not just a period of inactivity or a garbage collection of the waste products that the brain accumulated while we were awake. Quite the contrary: while we sleep, our brain remains active; it runs a specific algorithm that replays the important events it recorded during the previous day and gradually transfers them into a more efficient compartment of our memory.”

And if you don’t sleep properly and feel like shit, there is no way you are going to be able to learn such a mentally straining subject like informatics olympiad well. So please actually sleep at least 8 hours every day. Thanks.

References

$[1]$ Masataka Yoneda, [Tutorial] A way to Practice Competitive Programming : From Rating 1000 to 2400+

$[2]$ Masataka Yoneda, My winning theory in IOI 2018 & 2019 — Why I won 2 golds in IOI

$[3]$ Mateusz Radecki, My opinion on how to practice competitive programming

$[4]$ Aleksei Daniliuk, How to practice Competitive Programming [Um_nik version]

$[5]$ Tähvend Uustalu, Self-deception: maybe why you’re still grey after practicing every day

$[6]$ G. H. Hardy, A Mathematician’s Apology

$[7]$ W. T. Gowers, The Two Cultures of Mathematics.

$[8]$ Max Zhang, What Makes a Problem Hard?

$[9]$ George Polya, How to Solve It

$[10]$ Tricki, a repository of mathematical know-how

$[11]$ nor, How to learn better, and what most people don’t get about learning

$[12]$ Al Khan, How To Use Anki: An Efficient Tutorial For Beginners

$[13]$ Evan Chen, What leads to success at math contests?

$[14]$ Stanislas Dehaene, How We Learn: Why Brains Learn Better Than Any Machine . . . for Now

$[15]$ Terence Tao, Learn and relearn your field

$[16]$ Paul Lockhart, A Mathematician’s Lament

$[17]$ Terence Tao, There’s more to mathematics than rigour and proofs