A Collection of Flow and Matching Results from Scratch

I was reading Ramsey Theory $[1]$. In chapter 1.6, they had a section on corrolary of Ramsey’s Theorem.

Let $D(a+1,b+1)$ denote the minimium size of a poset such that there it is guaranteed that we can either find a chain of size $a+1$ and an anti-chain of size $b+1$.

Let $ES(a+1,b+1)$ denote the minimum size of a distinct array of distinct integers such that it is guaranteed that we can either LIS is at least $a+1$ or LDS is at least $b+1$.

But using Ramsey’s Theorem, we can show that $D(a+1,b+1), ES(a+1,b+1) \leq R(a+1,b+1)$, which is a very silly corollary of Ramsey’s Theorem. We know that from Dilworth’s Theorem and Erdős–Szekeres Theorem that $ES(a+1,b+1) = D(a+1,b+1) = ab+1$.

Dilworth’s theorem implies $D(a+1,b+1) \leq ab+1$. Suppose that there the maximum chain and anti-chain sizes are $a$ and $b$ respectively. Then, by Dilwroth’s theorem, there is a chain decomposition of $b$ disjoint chains. Each chain has $a$ elements. So there are at most $ab$ elements in the poset.

We also have $ES(a+1,b+1) \leq D(a+1,b+1)$. For the array $A$, the poset $(S,\leq)$ is defined as $u \leq_S v \iff (u \leq v \land A_u \leq A_v)$. A chain is a increasing subsequence. An anti-chain is a decreasing subsequence.

Actually, these inequalities are tight, because it is trivial to find a example to show that $ab < ES(a+1,b+1)$. Geometrically, take a $a \times b$ rectangle grid of points and rotate it slightly.

Anyways, until now, the only proof I knew of Erdős–Szekeres was by the pigeonhole argument given in $[2]$. But now I knew 2 more proofs. One was given above by using Dilworth and the other one was given when I read the original paper where it was proven in $[3]$. I read $[3]$ because it was the paper where Erdős–Szekeres showed the generalization of Happy Ending Problem had a bound of $\binom{2n-4}{n-2}+1$.

Anyways, I realized I didn’t know how to prove Dilworth so here is what I learnt from going down this rabbit hole… Here are some references and the appropriate things to read.

Ford-Fulkerson

See $[4]$.

Max-Flow Min-Cut Duality

See $[5]$, one should understand the constructive algorithm of generating the minimum cut from the residual graph.

I have been told by a lot of old people that in the heydays of Topcoder it was flow meta. Those old people will obviously be really good at flow modelling since it was necessary but now I feel like a complete noob at flow compared to them. During OCPC I just watched mhq do flow problems and all I could do was 👁️👄👁️👍

Unfortunately those heydays are over and flow barely appears in competitive programming. Unfortunately I don’t know how to use Topcoder to access their wealth of flow problems… perhaps there are 120230492384 examples of flow problems in Topcoder but I’m not aware of them.

So first mistake was that when I learnt about minimum cut, I was stuck thinking about optimally choosing a set of edges such that $S$ cannot reach $T$ without these edges. But instead, the more useful way to think about minimum cut is to choose sets $X$ and $Y = V-X$ such that $s \in X$ and $y \in T$ and then deleting all edges that goes $X \to Y$. And our goal is to optimize the choice of $X$.

The point is that we should not focus on the set of edges itself. Instead, focus on the partition $X$ and $Y$ that induces those edges.

Therefore, minimum cut allows you to solve the following problem, which I hope will feel more familiar to you. You need to construct a binary string $S$ of length $n$, the cost of the binary string is defined as followed:

- If $S_i = \texttt{0}$, you get $A_i$ penalty

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$, you get $B_i$ penalty

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$ and $S_j = \texttt{0}$, you get $C_{i,j}$ penalty

So basically $i \in X$ has $S_i = \texttt{1}$ and $i \in Y$ has $S_i = \texttt{0}$. Then we construct the following flow graph:

- $s \to i$ with cost $A_i$

- $i \to t$ with cost $B_i$

- $i \to j$ with cost $C_{i,j}$

Then our min cut corresponds to the answer to our problem. For some reason, my brain finds this easier to work with than thinking about $X$ and $Y$…

In the above formula, I have assumed that all of $A,B,C$ are non-negative. We cannot put neagtive weights into a flow graph and expect the graph to spit out the correct answer.

So what should we do if some of $A,B,C$ are negative? Notice that we can add a constant $M$ to both $A_i$ and $B_i$ as long as we subtract $M$ from our answer later. So we can transform the problem to one where $A_i$ and $B_i$ are non-negative. Unfortunately, we need to force a constraint on $C_{i,j}$ being non-negative as I don’t know how to handle it when it is negative.

We can write all flow networks in our binary string formulation and that we can write all binary string formulations as flow networks as long as $C_{i,j} \geq 0$. So we will forget that we are even working with flow networks and formulate our problem entirely using this binary string formulation. It is like when solving problems in 2-SAT. You do not need to care that we are attacking it with SCCs to transform the problem into one about 2-SAT. Same thing here.

Project Selection Problem

The project selection problem described in $[6]$. In short, you are given $n$ projects and $m$ machines. Each project has profit $p_i$ and machine machine has cost $q_i$. Each project has a set of machines that you must buy to complete the project. (Each machine, once purchased, can be used by all projects that requires it.)

Let the indices of our binary string be the set of all projects and machines. $S_i = \texttt{0}$ means we take the project/buy the machine and $S_i = \texttt{1}$ means we do not take the project/do not buy the machine.

To handle the profit of taking project $i$, we add the constraint:

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$, we get $-p_i$ penalty

To handle the cost of buying machine $i$, we add the constraints:

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$, we get $q_i$ penalty

If $i$ is a project and $j$ is a machine and getting the money for project $i$ requires buying machine $j$, then we have the constraint:

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$ and $S_j = \texttt{0}$, we get a $\infty$ penalty

So this problem is solvable using min cut.

ARC085C

Let $S_i = \texttt{0}$ if we don’t smash gem $i$ and $S_i = \texttt{1}$ if we smash gem $i$.

Then the costs are as follows:

- If $S_i = \texttt{0}$, we pay $-A_i$ penalty.

- If $i$ is a factor of $j$ and $S_i=\texttt{1}$ and $S_j = \texttt{0}$, we pay $\infty$ penalty.

ABC225G

There are 2 slightly different ways to do this problem.

For the first way, we can observe that we can uniquely identify all / diagonal by their bottom left corner and all \ diagonals by their bottom right corner. Then $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$ if we draw an X inside cell $(i,j)$.

Then the costs are as follows:

- If $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$, we pay $-A_{(i,j)}$ penalty

- If $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$ and $S_{(i+1,j-1)} = \texttt{0}$, we pay $C$ penalty

- If $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$ and $S_{(i+1,j+1)} = \texttt{0}$, we pay $C$ penalty

For the second way, consider paying $A_{(i,j)}-2C$ if you draw X on tile $(i,j)$ and then you get a refund of cost $C$ if there are X on both tiles $(i,j)$ and $(i+1,j-1)$ in addition to X on both tiles $(i,j)$ and $(i+1,j+1)$.

So let $S_{(i,j),-1}=\texttt{1}$ mean that we got the refund for placing X on both tiles $(i,j)$ and $(i+1,j-1)$ while $S_{(i,j),1}=\texttt{1}$ means that we got the refund for placing X on both tiles $(i,j)$ and $(i+1,j+1)$.

Then $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$ means that we placed X on the tile $(i,j)$.

Then the costs are as follows:

- If $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$, we pay $-A_{(i,j)}+2C$ penalty

- If $S_{(i,j),\pm 1} = \texttt{1}$, we pay $-C$ penalty

- If $S_{(i,j),\pm 1} = \texttt{1}$ and $S_{(i,j)}=\texttt{0}$, we pay $\infty$ penalty

- If $S_{(i,j),\pm1 } = \texttt{1}$ and $S_{(i+1,j\pm 1)}=\texttt{0}$, we pay $\infty$ penalty

Flipping the Constraints

Sometimes, the “natural” constraints are of the form:

- If $S_i = \texttt{0}$, you get $A_i$ penalty

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$, you get $B_i$ penalty

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$ and $S_j = \texttt{1}$, you get $C_{i,j}$ penalty (PAY ATTENTION: we have $S_j = \texttt{1}$ of $S_j = \texttt{0}$)

How we will convert them into the format that we need to min-cut is that realize that we can split the indices into sets $X$ and $Y=V-X$ such that constraints of type $C$ span $(X,Y)$. That is, if $C_{i,j} \neq 0$, then we have $i \in X$ and $j \in Y$.

Then to convert this into something we can handle with minimum cut, we can “flip” everyone in $Y$. Specifically:

- If $S_i =\texttt{0}$ and $i \in X$, you get $A_i$ penalty

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$ and $i \in X$, you get $B_i$ penalty

- If $S_i =\texttt{1}$ and $i \in Y$, you get $A_i$ penalty

- If $S_i =\texttt{0}$ and $i \in Y$, you get $B_i$ penalty

- If $S_i = \texttt{1}$ and $S_j = \texttt{0}$ and $i \in X$ and $j \in Y$, you get $C_{i,j}$ penalty

In the below problems, we will work with the “natural” formulation of the problem and leave it to the reader to turn it into the proper min-cut version.

ABC259

Here the indices are the set of rows and columns. We have $S_r = \texttt{1}$ if we chose row $r$ and $S_c = \texttt{1}$ if we chose column $c$.

Then the costs are as follows:

- If $S_r = \texttt{1}$, we pay $-\sum A_{r,i}$ penalty

- If $S_c = \texttt{1}$, we pay $-\sum A_{i,c}$ penalty

- If $S_r = \texttt{1}$ and $S_c = \texttt{1}$ and $A_{r,c} < 0$, we pay $\infty$ penalty

- If $S_r = \texttt{1}$ and $S_c = \texttt{1}$ and $A_{r,c} \geq 0$, we pay $A_{r,c}$ penalty

Then we simply set $X = {r}$ and $Y = {c}$ and all the constraints of type $C_{i,j}$ are between $X$ and $Y$.

ABC193F

We want to change this problem into one where we are minimising penalty so that $C_{i,j} \geq 0$. We will have penalty when two adjacent cells are the same color.

Denote $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$ if $(i,j)$ is colored black.

Then the costs are as follows:

- If $c_{i,j} = \texttt{B}$ and $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{0}$, we pay $-\infty$ penalty

- If $c_{i,j} = \texttt{W}$ and $S_{(i,j)} =\texttt{0}$, we pay $-\infty$ penalty

- If $S_{(i,j)} = \texttt{1}$ and $S_{(i \pm 1,j \pm 1)} = \texttt{1}$, we pay $1$ penalty

Now, the trick is to realize that if we have $X$ and $Y$ contain all the cells $(i,j)$ where the parity of $i+j$ is $0$ and $1$ respectively, then all constraints of type $C_{i,j}$ are between $X$ and $Y$. This is corresponds to a chessboard coloring.

ARC142E

Let $c_i$ denote the final strength of the wizard. First, an obvious constraint is that for all pairs $(x,y)$, we have $c_x,c_y \geq \min(b_x,b_y)$. Let $mn_i$ denote the minimum value of $a_i$ under this constraint.

If the above constraint is true, the only other constraint we need to worry about is that $\max(c_x,c_y) \geq \max(b_x,b_y)$.

Now notice that $c_i$ and $b_i$ are small. For the indices of our binary string, it makes sense to define $S_{(i,v)} = \texttt{1}$ iff $c_i < v$.

Then the costs are as follows:

- If $S_{(i,v)} = \texttt{0}$ and $a_i \leq v$, we pay a penalty $1$

- If $S_{(i,v)} = \texttt{1}$ and $S_{(i,v+1)} = \texttt{0}$, we pay a penalty $\infty$

- If $(x,y)$ is a pair and $S_{x,\max(b_x,b_y)} = \texttt{1}$ and $S_{y,\max(b_x,b_y)} = \texttt{1}$, then we pay penalty $\infty$

Unfortunately, we find sets $X$ and $Y$ such that all constraints of the last type are between $X$ and $Y$ so easily this time. Luckily, we can delete some constraints by making some observations.

Let $X$ be the set of wizards such that for all pairs $(x,y)$, we have $b_y < b_x$. Let $Y$ be the other wizard. For all wizards in $Y$, we can deduce that $a_i \geq b_i$, since there exists some pair $(x,y)$ such that $b_x \geq b_y$ so that $a_y \geq \min(b_x,b_y) = b_y$.

Now, the extra constraint that $\max(a_x,a_y) \geq \max(b_x,b_y)$ ends up being needed only for pairs where one is in $X$ and the other is in $Y$. There are no pairs that are both in $X$. And all pairs in $Y$ automatically fufil our additional constraint.

Therefore, all troublesome contstraints are between $X$ and $Y$ and we can use min cut here.

Calculating Max-Flow using Min-Cut

In the reverse of the section above, we sometimes flow graph where we are interested about the flow through the graph but computing the min-cut using ad-hoc techniques is easier.

However, there are some instances where we are interested in computing the maximum flow but computing the minimum cut is simpler. I have seen this idea inhttps://atcoder.jp/contests/arc125/tasks/arc125_e, https://codeforces.com/contest/724/problem/E and https://codeforces.com/problemset/problem/1919/F2 only (which I coordinated). Are there any problems that require this technique?

Gallai’s Theorem

See $[7]$.

From here on, let write:

- $mVC$ as minimum vertex cover

- $MIS$ as maximum independent set

- $mEC$ as minimum edge cover

- $MM$ as maximum matching

Then we have $mVC + MIS = mEC + MM = V$ along with the inequality $MM \leq mVC$.

Kőnig’s Theorem

Kőnig’s theorem makes the inequality $MM \leq mVC$ in Gallai’s Theorem tight. Although there is a constructive proof without flows as in $[8]$, but I am convinced by Kulkov as in $[9]$ that the only morally correct way to think about Kőnig’s thoerem is via min-cut max-flow. In fact, $[8]$ literally does the min cut construction algorithm but just uses ad-hoc method instead of saying it works because of the residual graph.

The construction is as follows. For a bipartite graph $(X,Y)$, defined two extra vertices $(s,t)$ for the flow network. Add the following edges:

- $s \to x$ with weight $1$

- $x \to y$ with weight $\infty$

- $y \to t$ with weight $1$

Then obviously, max flow is maximal matching and min cut is minimum vertex cover.

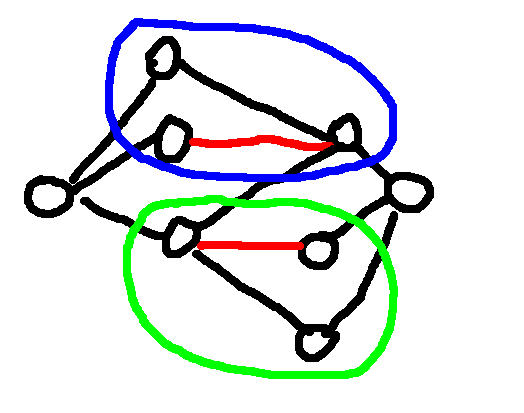

I want to note here that the diagrams shown in $[8]$ and $[9]$ might be misleading as there might be edges from $A_T$ to $B_S$ as desmonstrated below.

Now, with regards to our previous discussion on the project selection problem, we can note that this is the exact same problem if $X$ was projects and $Y$ were machines. The project selection problem then finds the set that maximizes $ \mid W \mid - \mid N_G(W) \mid$ for all $W \subseteq X$, which is the portion of the graph that causes us to waste $\mid W \mid - \mid N_G(W) \mid$ vertices on $X$. This segues right into Hall’s Theorem.

Hall’s Theorem

We can give a proof of Hall’s Theorem as a corollary of Kőnig’s theorem. Let the bipartite graph have partition $(X,Y)$ and we want to find a perfect matching covering all $X$.

$\exists W \subseteq X, ~ \mid W\mid > \mid N_G(W) \mid \to mVC < X$

Trivially no matching.

$mVC < X \to \exists W \subseteq X, ~ \mid W\mid > \mid N_G(W) \mid $

Suppose we have vertex cover $VC$ of size $mVC$ that is smaller than $X$. Then take $W = X \cap \overline{VC}$ and $Z = Y \cap VC$. We have $N_G(W) \subseteq Z$ or $VC$ is not a vertex cover. We also have $\mid Z\mid < \mid W\mid$ since $\mid VC\mid <\mid X\mid$. Therefore, $\mid N_G(W) \mid < \mid W\mid$.

Dilworth’s Theorem

Now, we can prove that Dilworth’s Theorem is equivalent to Kőnig’s Theorem. Let $MAC$ and $mPP$ the maximum anti-chain and minimum path partition for a poset.

Dilworth’s Theorem from Kőnig’s Theorem

Suppose we have the poset $(S,\leq)$ on $n$ elements

Define a bipartite graph $G=(U,V,E)$ with $U=V=S$, then edge $(u,v)$ exists iff $u < v$

Let the $mPP$ and $MM$ denote the minimum path partition on $S$ and maximum matching on $G$ respectively.

$mPP \leq n-MM$: Suppose that there is edge $(u,v)$ in a maximal matching, then they will be in the same chain.

$MM \geq n-mPP$: Each chain represents a total ordering $v_1 < v_2 < \ldots < v_k$ and we add the edge $(v_i,v_{i+1})$ into our matching.

Therefore, $mPP=n-MM$

Now let $MAC$ and $mVC$ denote the maximum antichain on $S$ and the minimum vertex cover on $G$ respectively.

$MAC \geq n-mVC$: we can construct an antichain from the set of vertices that are not selected in both $U$ or $V$ in the minimum vertex cover.

$ mVC \leq n-MAC $: Let $X$ be a maximal antichain. Consider each element $s \in \overline X$. Define $L_s = \{x \mid s < x\}$ and $R_s = \{x \mid x < s\}$. If $L_s \cup R_s = \varnothing$, then we can add $s$ into $X$. If both $L_s \neq \varnothing$ and $R_s \neq \varnothing$, then we can find $x_1 < s < x_2$ which is absurd. Therefore, we can uniquely identify each element $s $ as either $\texttt{L}$ or $\texttt{R}$ depending on which of $L_s$ and $R_s$ is empty. To construct our vertex cover, place $s$ in $U$ or $V$ depending on whether it is $\texttt{L}$ or $\texttt{R}$. Now, we have to prove that this covers all edges $(u,v)$. If $u \in X$, then $v \in R_u$. Similarly if $v \in X$, then $u \in L_v$. Now suppose $u,v \notin X$, and that $u$ and $v$ are type $\texttt{R}$ and $\texttt{L}$ respectively. This implies $x_1<u<v<x_2$ which is absurd.

Therefore, $MAC=n-mVC$

Therefore, we have proved Dilworth’s theorem that $mPP = MAC$

Kőnig’s Theorem from Dilworth’s Theorem

Suppose we have a bipartite graph $G=(U,V,E)$. Let $sz = \mid U\mid +\mid V\mid$

Define a poset $(S,\leq)$ with $S = U \cup V$ and $u < v $ if edge $(u,v)$ exists.

Let the $MM$ and $mPP$ denote the maximum matching on $G$ and the minimum path partition on $S$ respectively.

$mPP \leq sz-MM$: Suppose that there is edge $(u,v)$ in a maximal matching, then they will be in the same chain.

$MM \geq sz-mPP$: Each chain has either size $1$ or $2$. If it has size $2$ and of the form $u<v$, add $(u,v)$ into our matching.

Therefore, $MM = sz-mPP$

Now let $mVC$ and $MAC$ denote the minimum vertex cover on $G$ and the maximum antichain on $S$ respectively.

By taking complements of each other, it is easy to see that $mVC=sz-MAC$

Therefore, we have proved Kőnig’s theorem that $MM = mVC$

Berge’s Theorem

See $[7]$ and $[10]$.

An $M$-augmenting path is a sequence of distinct vertices $v_1,v_2,\ldots,v_{2k}$ such that $v_1$ and $v_{2k}$ are unmatched and $v_{2i},v_{2i+1}$ are matched in $M$. We want to make clear that augmenting paths is only defined with respect to the matching $M$.

Berger’s Theorem is that a matching $M$ is maximum iff there are no augmenting paths. See $[7]$.

The main idea here is to take two matchings $M$ and $M’$ and consider their symmetric difference $M \Delta M’$ (union also works I guess).

If we consider their symmetric difference, then all connected components are either cycles or paths. These both are alternating between edges in $M$ and $M’$.

Then to prove Berger’s theorem, just suppose that $M’$ has more edges than $M$. Then in some connected component of $M \Delta M’$, there are more $M’$ edges than $M$ edges. This must be a path, so we found an augmenting path.

This is the basis of all matching algorithms.

Bipartite Matching (Kuhn’s Algorithm)

See $[7]$ and $[10]$.

Let $(X,Y)$ be the bipartite graph. Let $S$ denote the set of paths that start from a unmatched vertex in $X$ and alternates between edges in $M$ and not in $M$. There is no restriction that the path needs to end in an unmatched vertex, as in a augmenting path. Then there is an augmenting path iff there is a unmatched vertex in $Y \cap S$. It is easy to construct $S$ each time using DFS.

By the way, you can prove Hall’s Theorem by showing that Kuhn’s always find a prefect matching, to prove $\forall W \subseteq X, ~ \mid W\mid \leq \mid N_G(W) \mid \to MM = V$. Take any free $x \in X$ and let $S$ be the set of vertices such that it is connected to $x$ by augmenting paths. Then suppose that $Y \cap S$ contains no free vertices so that we cannot augment the graph further. Then we must have $\mid X \cap S\mid \geq \mid Y \cap S\mid +1$ since all vertices in $Y \cap S$ have their corresponding matched vertex in $X \cap S$. and $X \cap S$ also contains $x$. However, by our condition for Hall’s Theorem, we also have $\mid X \cap S\mid \leq \mid Y \cap S\mid $. Contradiction.

General Matching (Blossom’s Algorithm)

See $[7]$ and $[11]$.

The problem with doing the algorithm mentioned above is that we might find an augmenting path that contains repeated vertices due to the fact that odd cycles exists. So we need to contract odd cycles (called Blossoms).

Now, we should note that Blossoms are only defined relative to the matching $M$. There is a reason we need to “lift” all blossom back to the original graph when we apply a new augmenting path. It is because an $M$-blossom is not necessarily an $M’$-blossom. A counterexample can be seen in figure $4$ of $[11]$.

Now, there is another $O(n^3)$ general matching algorithm that is described in $[12]$ but I shall not claim to understand it yet…

Factor-Critical Graphs

A factor-critical graph is a graph $G$ where the removal of any vertex allows the remaining induced subgraph to have a perfect matching.

Here are some equivalent formulations:

- every vertex $v$ in $G$ has a maximum matching that misses $v$, see $[7]$ and $[11]$

- $G$ has a odd ear decomposition starting from an odd cycles, see $[11]$

The proof of the first formulation is very important lemma in the proofs of the following Tutte-Berge Formula in $[7]$ and $[11]$.

Tutte-Berge Formula and Edmond-Gallai Decomposition

So there are $2$ different ways to approach this and the next section. They are given in $[11]$ and $[13]$. Their proofs are roughly the same I guess? $[7]$ also proved Tutte-Berge in the same way as $[11]$ but does not go on to Edmond-Gallai. All proofs make extensive use of factor-critical graphs.

The proofs of $[7]$ and $[11]$ rely on the fact that $G$ is factor critical iff every vertex $v$ in $G$ has a maximum matching that misses $v$. Then just split into $2$ cases, there is a vertex $v$ that is contained in every maximum matching, or vertices $v$ are missed by some maximum matching and $G$ is factor critical.

While $[13]$ just proves directly that the maximal set $S$ that minimizes the Tutte-Berge formula splits the rest of the graph into factor-critical components.

Then for Edmond-Gallai, $[13]$ proves that constructs the decomposition $(A,C,D)$ from the $S$ that we found earlier. Whereas $[11]$ starts from scratch from an arbitrary matching along with contractions by Blossom’s algorithm.

Anyways, for the sake of future reference here is the Edmond-Gallai Decomposition.

The decomposition $(A,C,D)$ is as follows:

- $D$ is the set of vertices where there exists a maximum matching that does not use them

- $A$ is the vertices that are connected to $D$

- $C$ is the rest of the vertices

In $[13]$, let $S$ be the set we described earlier. Then the rest of the graph $T$ are all factor critical. We will shrink the components into single points and use Hall’s theorem. Then, let $H$ be the maximum set of $S$ such that $\mid H\mid = \mid N(H)\mid $ is true. So that means we are able to miss any point in $T \setminus N(H)$. So $D = T \setminus N(H)$, $A = H$ and $C$ is everything else.

In $[11]$, take any maximum matching $M$. $D$ is the vertices that are connected by any alternating path of even length from an unmatched vertex, $A$ is the vertices that are connected by only alternating paths of odd length and $C$ are the rest of the vertices. We want to work with the contracted graph from Blossom’s algorithm because now we show that all vertices in a contracted blossom are all even. And there are also no edges between even vertices (or Blossoms). Effectively, we kind of just created the same situation as above where we contracted all components of $T$ above into single points.

Some properties of the $(A,C,D)$ decompositions:

- all components in $D$ are factor critical. In a maximum matching we use that matching and maybe one vertex get matching to something in $A$

- all components in $C$ are perfectly matched in a maximum matching

- obviously from above, $C$ and $D$ are respectively the even and odd components of $A \setminus G$

- all vertices in $A$ are matched to some component in $D$ in a maximum matching

- each subset $X \subseteq A$ has neighbours in at least $\mid X\mid +1$ components in $D$

- $A$ is a possible set that minimizes Tutte-Berge formula

- The number of vertices that are not matched in the maximum matching is the number of components in $D$ minus the number of vertices in $A$

Some Interesting Problems

These are taken from $[7]$

- For each $k>1$, construct a $k$-regular graph without a perfect matching

- Prove that each $2k$-regular graph contains a $2$-factor

- Prove that each $3$-regular graph without bridges contains a prefect matching

References

I would not be surprised if many links will be broken in a few years… un lucky

$[1]$ R. Graham, B. Rothschild and J. Spencer, Ramsey Theory http://people.dm.unipi.it/dinasso/ULTRABIBLIO/Graham_Rothschild_Spencer%20-%20Ramsey%20Theory%20(2nd%20edition).pdf

$[2]$ A. Seidenberg, A Simple Proof of a Theorem of Erdös and Szekeres, https://academic.oup.com/jlms/article-abstract/s1-34/3/352/847946

$[3]$ P. Erdős and G. Szekeres, A Combinatorial Problem in Geometry, http://www.numdam.org/item/CM_1935__2__463_0.pdf

$[4]$ T. Uustalu, [Tutorial] My way of understanding Dinitz’s (“Dinic’s”) algorithm, https://codeforces.com/blog/entry/104960

$[5]$ T. Uustalu, [Tutorial] The residual graph and working with the set of all minimum cuts, https://codeforces.com/blog/entry/104960

$[6]$ Wikipedia, Max-flow min-cut theorem (Project selection problem), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max-flow_min-cut_theorem#Project_selection_problem

$[7]$ A. Schrijver, Matchings and coverings, https://homepages.cwi.nl/~lex/files/agt1.pdf

$[8]$ Wikipedia, Kőnig’s theorem (graph theory) (Constructive proof without flow concepts), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C5%91nig%27s_theorem_(graph_theory)#Constructive_proof_without_flow_concepts

$[9]$ O. Kulkov, Kőnig’s and Hall’s theorems through minimum cut in bipartite graphs, https://codeforces.com/blog/entry/105697

$[10]$ CP Algorithms, Kuhn’s Algorithm for Maximum Bipartite Matching, https://cp-algorithms.com/graph/kuhn_maximum_bipartite_matching.html

$[11]$ M. X. Goemans, Lectures on Nonbipartite Matchings, https://math.mit.edu/~goemans/18455S20/lecs-matching.pdf

$[12]$ O. Kulkov, Randomized general matching with Tutte matrix, https://codeforces.com/blog/entry/92400

$[13]$ D. B. West, A short proof of the Berge–Tutte Formula and the Gallai–Edmonds Structure Theorem, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195669811000187