STEP 3

I grinded like crazy for STEP 3 in the past week, you can see the amount of paper I used below. And it does not include the paper I used in preparation for STEP 2.

I did the stupid Singaporean strategy and just did a 10 year series of STEP 3 papers (2015-2022, almost 10 year series).

I think I should have done decently? I am expecting S,S…

For STEP3, I did the problems in the order of 11,12a,1,7,5,2,12b.

Question 12 was bashing a bunch of integrals (which I overcomplicated alot) and I only returned to it at the end of the exam when I had an entire 30 mins left. I spent the entire 30 mins on parts (ii) and (iii)…

There are some discussions on r/6thForm at https://www.reddit.com/r/6thForm/comments/1dnafh8/comment/la17izv.

1

Very straight forward problem, thankfully I could do this quickly to save time.

The premise of this problem is to simplify sums of the form $\sum\limits_{r=1}^\infty\frac{1}{poly(r)}$ using partial fractions and telescoping sums.

You are given the result that $\sum\limits_{r=1}^\infty\frac{1}{r^2} = \frac{\pi^2}{6}$.

The first part asks you to find $\sum\limits_{r=1}^\infty\frac{1}{r^2(r+1)} = \sum\limits_{r=1}^\infty \frac{1}{r^2} + \frac{1}{r+1} - \frac{1}{r} = \frac{\pi^2}{6}-1$.

The rest of the problem is about the same. Bash the partial fraction then do telescoping, not very interesting.

2

This was the last problem I did in section A, it looked not bad but I still have no idea how to do part (iv) correctly…

In this problem you have to handle inequalities of the form $\sqrt{ax^2 + bx + c} \leq \lvert mx+c \rvert$.

For part (i), you solve $\sqrt{4x^2-8+64} \leq \lvert x+8\rvert$ and $\sqrt{4x^2-8+64} \leq \lvert 3x-8\rvert$

For part (ii), you sketch $\sqrt{4x^2-8+64}$ and $2(x-1)$ on the same graph, where asymptotically, $\sqrt{4x^2-8+64} \sim 2(x-1)$

For part (iii), you solve $\sqrt{4x^2-8+64} \leq \lvert mx+c \rvert$ such that the solution is $3 \leq x$

For part (iv), which I completely messed up, which I realized after the test when discussing with others. You solve $\sqrt{x^2+px+q} \leq \lvert mx+c\rvert$ where the solutions are $-5 \leq x \leq 1$ and $5 \leq x \leq 7$. But I think that I have recalled the problem wrongly, since I cannot find any possible values where the inequality holds on 2 disjoint regions. I think it must be allowed that $x^2 + px + q<0$, so that $1<x<5$ is just the region where $\sqrt{x^2+px+q}$ does not exists? But I really am not sure. I think there is a high chance that I just recalled the problem wrongly.

EDIT: indeed I recalled the problem wrongly. The inequality to solve is $\lvert x^2+px+q \rvert \leq mx+c$. I think I was confused cause the person I was discussing with told me he had $6=\binom{4}{2}$ cases. But I think he did not realize that we can figure out at the start that the outer numbers $-5$ and $7$ belong to $x^2+px+q = mx+c$ and the inner numbers $1$ and $5$ belong to $-(x^2+px+q)=mx+c$.

Anyways, after solving $x^2+(p-m)x+(q-c)=(x-7)(x+5)=x^2-2x-35$ and $x^2+(p+m)x+(q+c)=(x-1)(x-5)=x^2-6x+5$, we end up with the inequality $\lvert x^2-4x-15 \rvert \leq -2x+20$ which I checked on desmos.

5

I was grinding DEs, so I decided to do the DE question. Worked out I guess. As expected, it was a boring problem where you just bash the algebra. I got abit stuck on the last part until I realized that a counterexample is easy to find.

Let $M$ and $N$ be $2 \times 2$ matrices.

In part (a), we need to prove $\text{tr}(MN)=\text{tr}(NM)$ and $\text{tr}(N+M)=\text{tr}(N)+\text{tr}(M)$ which is just algebra bashing, but free points.

There was also another eqution here that you had to prove, but I forgot. It was more algebra bashing.

In part (b), we analyze the DE $\frac{d}{dt} M = MN-NM$, where elements of the matrices are functions of $t$.

We had to prove that $\text{det}(M)$, $\text{tr}(M)$ and $\text{tr}(M^2)$ are all constant, which is just even more bashing using results from part (a).

In part (c), we analyze the DE $\frac{d}{dt} M = MN$. We need to prove or disprove that if $\text{tr}(M)$ is non-zero but constant, then $\text{tr}(N)$ is constant. I realized that we can write $N = M^{-1} \frac{d}{dt} M$ and make $M$ whatever nonsense function we want and it will probably work. I think I chose $M = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & t \\ t &1 \end{pmatrix}$.

7

In this problem, we are working on a proof that $e$ is irrational, which I find very interesting. I somewhat recall the proof from Baby Rudin and this proof seems abit familiar.

Let:

- $f (n) = \frac{1}{(n+1)} + \frac{1}{(n+1)(n+2)} + \frac{1}{(n+1)(n+2)(n+3)} + \ldots$

- $g (n) = \frac{1}{(n+1)} - \frac{1}{(n+1)(n+2)} + \frac{1}{(n+1)(n+2)(n+3)} - \ldots$

First, we prove that $0 < f(n) < \frac{1}{n}$ and $0 < g(n) < \frac{1}{n+1}$, the latter one is quite stupid to prove cause I split into odd and even cases.

Then we prove that $(2n)!e - f(2n)$ and $\frac{(2n)!}{e} + g(2n)$ are both integers.

Finally, we assume $e^2 = \frac{p}{q}$ for some $p,q \in \mathbb{Z}$. So that $qe = \frac{p}{e}$.

Now, $q \cdot f(2n) + p \cdot g(2n)$ must be an integer also, since $q \cdot f(2n) + p \cdot g(2n) + q((2n)!e - f(2n)) - p(\frac{(2n)!}{e} + g(2n)) = (2n)!(qe-\frac{p}{e}) =0$ is an integer.

Now, for some very large $M$, $0<q \cdot f(2M) + p \cdot g(2M)<1$, so that $q \cdot f(2M) + p \cdot g(2M)$ cannot possibly be an integer.

By contradiction, $e$ is irrational.

A very neat proof I think.

11

Standard combinatorics problems.

You play a game where you pay £n and you flip a fair coin $2n$ times. Let there be $a$ heads and $b$ tails, then you will get back £$\max(a,b)$. You need to find your expected winnings and then find the optimal $\frac{E(\text{winnings})}{n}$, which quite stupidly is $n=1$ since $E(\text{winnings}) = n(1+\frac{1}{2^{2n}} \binom{2n}{n})$.

The question did not explicitly say that the smallest possible $n$ is $1$, so I wrote that I assume that $1 \leq n$ is the lower bound, but it shouldn’t be a big issue I guess?

12

This was calculus hell for me when I was doing the test but now that I am looking at it again, I could probably have done it a lot better.

Here, we are concerned with calculating the expected distance from the origin of a point chosen randomly from the square $[0,1]^2$.

Let $R$ be the random vairable of this distance. We will calculate the cdf of $R$ first which is part (i).

For $0 \leq r \leq 1$, $P(R \leq r) = \frac{\pi r^2}{4}$

For $1 \leq r \leq \sqrt{2}$, $P(R \leq r) = \frac{\pi r^2}{4} + \sqrt{r^2-1} - r^2 \arccos(\frac{1}{r})$, where the later is obtained from $\int_{1}^r \sqrt{r^2-x^2} \, dx$.

Now for part (ii), to calculate $E(R)$, the way that I usually do is $E(R)=\int r \cdot \frac{d}{dr} P(R \leq r)\, dr$, which I managed to calculate during the test but is super long winded because of how complicated the terms are.

Instead I realized during the test that $E(R)=\int 1- P(R \leq r)\, dr$, but it did not seem correct because I panicked and did not know how to integrate $r^2 \arccos(\frac{1}{r})$… then I skipped this problem for section A.

When I returned, I actually did part (iii) first, which was evaluating $E(R) = \frac{2}{3}\int\limits_1^{\sqrt{2}} \frac{r^2}{\sqrt{r^2-1}} \, dr$ first. I stupidly tried to do integration by parts where $I = \int \frac{r^2}{\sqrt{r^2-1}}\, dr = \int r \cdot \frac{r}{\sqrt{r^2-1}}\, dr = r \sqrt{r^2-1} - \int \sqrt{r^2-1} \, dr = r \sqrt{r^2-1} - \int \frac{r^2-1}{\sqrt{r^2-1}} \, dr$

So that you get $2I = r \sqrt{r^2-1} + \int \frac{1}{\sqrt{r^2-1}} \, dr$, so you still get this stupid integral of $\frac{1}{r^2-1}$ inside the fraction. It was here that I realized we just need to substitute $r = \cosh(\theta)$, so that $\int \frac{1}{\sqrt{r^2-1}} \, dr = \text{arccosh}(\theta)$.

But actually, you can substitute $r=\cosh(\theta)$ in the very beginning.

$\int \frac{r^2}{\sqrt{r^2-1}}\, dr = \int \sinh \theta \frac{\cosh^2 \theta}{\sinh \theta}\, d\theta = \int \cosh^2 \theta \, d\theta = \frac{\cosh(4 \theta)}{4} + \frac{\theta}{2}$

Well, whatever.

Also, I didn’t know the formula that $\text{arccosh}(x) = \ln(x^2 + \sqrt{x^2-1})$, but well, I just looked at the question and saw that the value was $\ln(\sqrt{2}+1)$, so I just pretended that I magic eye that $\cosh(\ln(\sqrt{2}+1)) = \sqrt{2}$.

Anyways, back to part (ii), let us prove that $E(R)=\int\limits_0^\infty 1- P(R \leq r)\, dr = \int\limits_0^\infty r \cdot \frac{d}{dr} P(R \leq r)\, dr$.

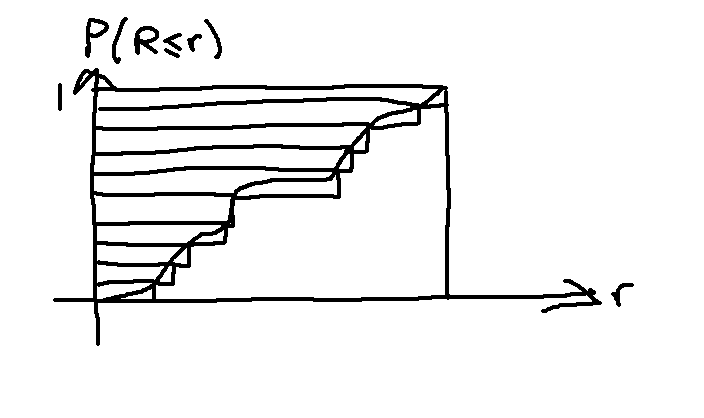

First, a visual proof that $E(R)=\int 1- P(R \leq r)\, dr$, assuming that $R \geq 0$, if $R$ can possibly be negative, it is easy to modify.

Alternatively, we can handwave an algebraic manipulation. Let the pdf be $p(r)$, so that $P(R \leq r) = \int\limits_0^r p(r) \, dr$.

We want to prove that $\int\limits_0^\infty 1- P(R \leq r)\, dr = \int\limits_0^\infty r \cdot p(r) \, dr $.

$\begin{align} \int\limits_0^\infty 1- P(R \leq r)\, dr &= \int\limits_0^\infty 1- \int\limits_0^r p(s) \, ds \, dr \\ &= \int\limits_0^\infty \int\limits_r^\infty p(s) \, ds \, dr \\ &= \int\limits_0^\infty \int\limits_0^s p(s) \, dr \, ds \\ &= \int\limits_0^\infty s p(s) \, ds \end{align}$

Basically, the intuitive proof.

Anyways, another lesson I learnt from this problem is about calculating $\frac{d}{dt} \arccos(t)$. I have memorized that $\frac{d}{dt} \arcsin(t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}$ but have never used $\frac{d}{dt} \arccos(t)$ before. I know that I can derive it but I was panicking and my mind went black before I skipped this problem.

Anyways, when I went back to this problem, I calmed down abit and realized that on the principle domain, $\cos(\theta)$ is basically $-\sin(\theta)$, but translated along the $x$-axis. So it must be that $\frac{d}{dt} \arccos(t) = -\frac{d}{dt} \arcsin(t) = - \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}$. Yay, crisis averted,

I probably spent almost an hour entirely on this problem. I think I must be conscious about thinking how to tackle such calculations before doing stupid things and wasting time. Because evidently, I wasted a lot of time. If I was more calm when doing this question, I would probably finish it faster and with neater handwriting. I only finished writing everything a few minutes before the time was up…