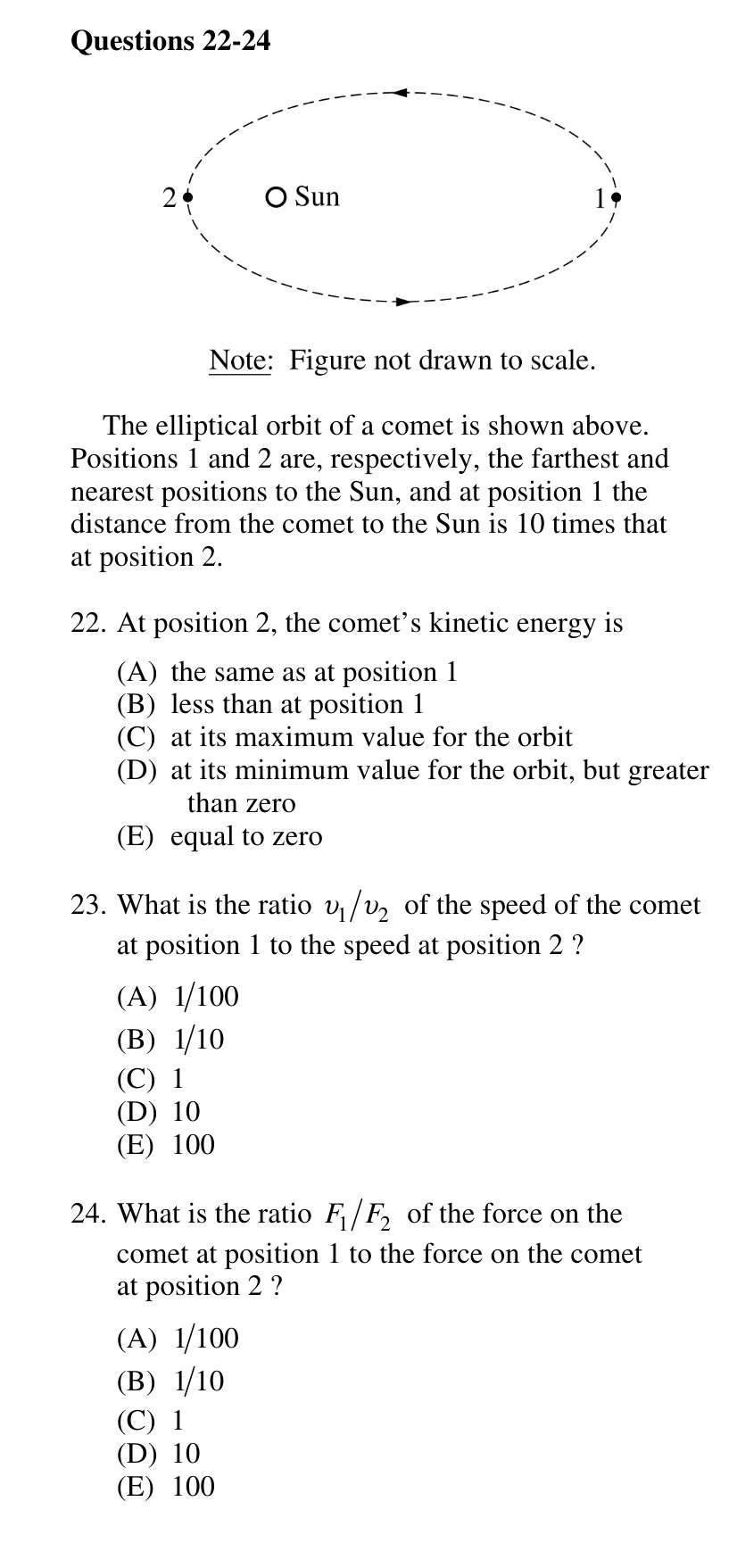

Elliptical Orbits

I couldn’t solve the below problem which is found in the AP Phys C: Mech 2012 Practice Exam so I will now write a blog post about elliptical orbits.

Definition of Ellipse

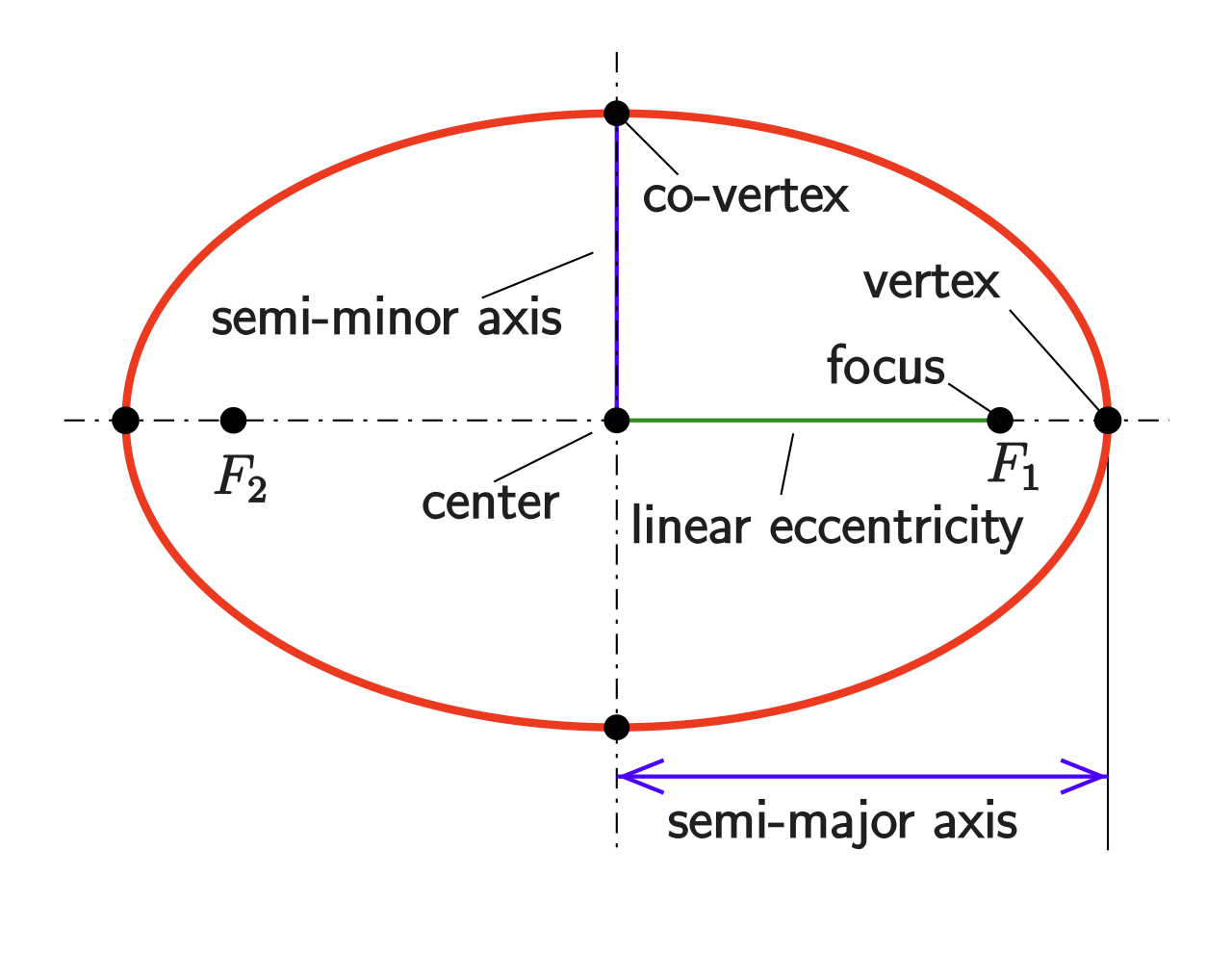

An ellipse is uniquely defined from $2$ chosen foci (possibly same) and a distance $d$. The perimeter of the ellipse if the locus of points whose sum of distance to the $2$ chosen foci is $d$. Since the ellipse have $5$ degrees of freedom (two pairs of coordinates from the foci and the distance $d$), $5$ points uniquely determine a ellipse.

Alternatively, the ellipse can also be viewed as a stretched circle with the equation $(\frac xa)^2 + (\frac yb)^2 = 1$, so that the points are given by the curve $(x,y) = (a \cos \theta, b \sin \theta)$. If $a \geq b$, the foci are at $(\pm c,0)$. Since $(a,0)$ is on the ellipse, we have $d=2a$. Therefore, by considering that $(0,b)$ is on the ellipse, $2\sqrt{c^2 + b^2} = 2a$. Clearly, $c = \sqrt{a^2-b^2}$ satisfies the equation.

To verify that it is an ellipse, we will have to verify that $\sqrt{(a \cos \theta + \sqrt{a^2-b^2})^2 + (b \sin \theta)^2} + \sqrt{(a \cos \theta - \sqrt{a^2-b^2})^2 + (b \sin \theta)^2} = 2a$.

$\begin{align}\sqrt{(a \cos \theta \pm \sqrt{a^2-b^2})^2 + (b \sin \theta)^2} &= \sqrt{a^2 \cos^2\theta \pm 2a\sqrt{a^2-b^2} \cos \theta + a^2-b^2 + b^2 \sin^2 \theta} \\ &= \sqrt{a^2 \cos^2\theta \pm 2a\sqrt{a^2-b^2} \cos \theta + a^2 - b^2 \cos^2 \theta} \\ & = \sqrt{(a^2-b^2) \cos^2\theta \pm 2a\sqrt{a^2-b^2} \cos \theta + a^2} \\ &= a \pm \sqrt{a^2 - b^2} \cos \theta \end{align}$

Therefore, the original statement is clearly true.

The eccentricity of the ellipse is defined as $e = \sqrt{1 - \frac{b^2}{a^2}}$. Notice that for a circle, $e=0$. As $e$ increases to $1$, the ellipse gets more stretched.

Focus-to-Focus Property of Ellipses

Ellipses have a focus to focus property, where if a pool table was elliptical, a ball released on one focal point will always pass through the other focal point. In other words, for a point $P$ on the ellipse, the normal at point $P$ bisects the lines $\overline{PF_1}$ and $\overline{PF_2}$.

The classic analytic geometry proof is below. Let the ellipse be defined by the points whose sum of distances from $F_1$ and $F_2$ is $2a$.

- Construct point $L$ which is the extension from of the line $\overline{PF_1}$ such that $\lvert \overline{PL}\rvert = \lvert \overline{PF_2}\rvert$.

- Construct line $w$ that is perpendicular to the bisector of $\angle F_1PF_2$. $\omega$ is a angle bisector of $\angle F_2PL$.

- We will show that the intersection of $w$ with the ellipse is only a single point, so that $w$ is tangent to the ellipse.

- Choose a point $Q$ that is not equal to $P$. $\lvert \overline{QF_1} \rvert + \lvert \overline{QF_2}\rvert = \lvert \overline{QF_1} \rvert + \lvert \overline{QL}\rvert > \lvert \overline{F_1L}\rvert = 2a$, where the last inequality is due to triangle inequality.

- Since $\lvert \overline{QF_1} \rvert + \lvert \overline{QF_2}\rvert > 2a$, $Q$ is outside the ellipse.

- Therefore, $w$ is tangent to the ellipse and the normal at point $P$ indeed bisects the lines $\overline{PF_1}$ and $\overline{PF_2}$.

Here is proof by bashing synthetic geometry because why not. We will assume that we are working with the equation $(\frac xa)^2 + (\frac yb)^2 = 1$.

Suppose that the ball strikes the surface at angle $\theta$ from the origin, which is at point $R = (a \cos \theta, b \sin \theta)$.

From the equation $f(x,y) = (\frac xa)^2 + (\frac yb)^2 = 1$, we have $\nabla = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \end{pmatrix} = 2 \begin{pmatrix} \frac{2x}{a^2} \\ \frac{2y}{b^2} \end{pmatrix} = 2 \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\cos \theta}{a} \\ \frac{\sin \theta}{b} \end{pmatrix}$.

After scaling all vectors, $\nabla$ should be the average of $\overrightarrow{F_+R}$ and $\overrightarrow{F_-R}$. Where $F_\pm = (\pm \sqrt{a^2-b^2},0)$.

From earlier, we know that $d_\pm = \lvert \overrightarrow{F_\pm R} \rvert = a \pm \sqrt{a^2 - b^2} \cos \theta$.

Therefore, we have $d_- \cdot \overrightarrow{F_+R} + d_+ \cdot \overrightarrow{F_-R} = k \cdot \nabla$. One can verify that $k = \frac{1}{2ab^2}$ satisfies the equation.

Kepler’s Second Law

Thank you to nor for discussing this part with me. You can find his blog at https://nor-blog.codeberg.page/.

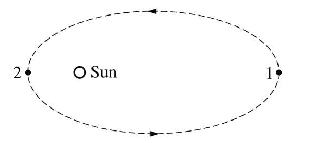

Firstly, from Kepler’s second law, we know that the line between the sun and the planet sweeps out an equal area over an equal time interval. The proof of this is through angular momentum.

Let $x_{CM}$ be the position of the center of mass of the entire system. The center of mass is somewhere on the line between the sun and the planet. By conversation of angular momentum, $I \omega$ is a constant value. $I\omega = mr^2 \cdot \frac{v}{r} = mvr$, which is proportional to $vr$.

But we need to be careful about this $v$ value here. It is not refering to the actual velocity $v$ in the diagram above but actually the perpendicular component of the velocity $v_\perp$ only. For most points, $v \neq v_\perp$. The only $2$ points where $v = v_\perp$ are those points that are on the line between the $2$ foci of the ellipse, which just happen to be the $2$ points given in the AP question above.

Total Energy of Planet

Let us assume that the mass of the sun is much larger than the mass of the planet.

By conservation of energy, we know that $\frac{1}{2} mv^2 - \frac{GMm}{r}$ is a constant.

Suppose that the distance from the sun to points $1$ and $2$ respectively are $a$ and $b$ respectively. From earlier, we know that $v_1r_1 = v_2r_2$.

Therefore, $\frac{1}{2} mv_1^2 - \frac{GMm}{r_1} = \frac{1}{2} mv_2^2 - \frac{GMm}{r_2} = \frac{1}{2} m(\frac{a}{b}v_1)^2 - \frac{GMm}{\frac{b}{a} r_1}$.

$\frac{1}{2} (1-(\frac{a}{b})^2) v_1^2 = \frac{GM}{r_1} (1 - \frac{a}{b})$, so that $\frac{1}{2} v_1^2 = \frac{GM}{r_1} \frac{1}{1+\frac{a}{b}}$.

We obtain $\frac{1}{2} mv_1^2 - \frac{GMm}{r_1} = \frac{GMm}{r_1} (\frac{1}{1+\frac ab} -1) = \frac{GMm}{r_1} (\frac{-a}{a+b}) = -\frac{GMm}{a+b}$.

Recall that the total energy of a circular orbit is $ - \frac{GMm}{2r}$. Observe that if we take $r$ as the semi-major axis, then this equation holds for ellipses.