Statistics

Combinatorics

$n!$ is the number of ways to arrange $n$ objects in a line

$^nC_r = \frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}$ is the number of ways to choose $r$ objects from $n$ objects if the order of the $r$ objects does not matter

$^nP_r = \frac{n!}{(n-r)!} = ^nC_r \cdot r!$ is the number of ways to choose $r$ objects from $n$ objects if the order of the $r$ objects matter

Probability

$P(A) = \frac{n(A)}{n(S)}$ is the probability that outcome $A$ happens, where $S$ denotes the sample space of events.

Obviously, we have $0 \leq P(A) \leq 1$.

$A^c$ is defined as the opposite of the outcome $A$, so that $P(A^c) = 1 - P(A)$.

$A \cup B$ denotes that both outcomes $A$ and $B$ happen while $A \cap B$ denotes that at least one of $A$ or $B$ happens.

$A$ and $B$ are disjoint if $P(A \cap B)=0$ or $P(A \cup B) = P(A)+P(B)$.

$A$ and $B$ are independent if $P(A \cap B) = P(A) \cdot P(B)$ and $P(A \cup B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A) \cdot P(B)$.

$P(A\mid B) = \frac{P(A \cup B)}{P(B)}$ is defined as the probability that $A$ happens given that $B$ happens. If $A$ and $B$ are disjoint or independent, then $P(A\mid B)$ is $0$ and $P(A)$ respectively.

Bayes’ theorem: $P(A \mid B) = \frac{P(B\mid A) \cdot P(A)}{P(B)}$.

Random Variables

A random variable $X$ is a variable that takes on state $x_i$ with probability $p_i$. So we can define $X$ by the lists $x$ and $p$. $0 \leq p_i \leq 1$ and $\sum p_i = 1$ must be satisfied. Here, we usually have $x_i \in \mathbb{R}$.

The expected value of a random variable is $E(X) = \sum x_i \cdot P(X = x_i) = \sum x_i \cdot p_i$. It can also be called the mean of the distribution $X$, which we denote $\mu_X$.

Note that the random variable can be put into a function like $X^2-X+3$ or $\sin(X)$.

Some properties of $E(X)$:

- $E(a)=a$

- $E(aX) = aE(X)$

- $E(X \pm Y) = E(X) \pm E(Y)$, known as linearity of expectation

- Generally, $E(X \cdot Y) \neq E(X) \cdot E(Y)$.

Define the variance of a random variable as $\text{Var}(X) = E((X-E(X))^2) = E(X^2) - E(X)^2$. In other words, it is the average squared deviation of the mean. We square the deviation so that the variance is positive, but we can also take the absolute value. We square the deviation because the Math is easier to do than absolute value. Usually, we denote the above quantity as $Var(X) = \sigma_X^2$, where $\sigma_X$ denotes the standard deviation of $X$. Note that $\sigma_X$ will have the same units as $X$.

Some properties of $\text{Var}(X)$:

- $\text{Var}(a) =0$

- $\text{Var}(aX) = a^2 \text{Var}(X)$

- $\text{Var}(X+a) = \text{Var}(X)$

- $\text{Var}(X \pm Y) = \text{Var}(X) + \text{Var}(Y)$, if $X$ and $Y$ are independent

Common Discrete Distributions

Bernoulli Distribution

There are only two outcomes, success and failure, where success happens with probability $p$.

$P(X=x) = \begin{cases}p, &\text{ if } x=1 \\ q,& \text{ if } x=0\end{cases}$

For brevity, we will define $q=1-p$.

Binomial Distribution

If the above distribution where success happens with probability $p$ was repeated $n$ times independently, we get a binomial distribution $X \sim B(n,p)$.

We say a distribution is approximately a binomial distribution if the probability for each of the $n$ steps are not independent but knowing the results of the previous steps has negligible effect on the result of the current step.

For instance, consider drawing $n$ balls from a collection of $a$ red and $b$ blue balls. The number of red balls in this distribution is approximately $B(n, \frac{a}{a+b})$, if $n \ll a+b$. We consider a distribution to be approximately binomial if the popular is at least $10$ times larger than the sample.

$X$ is described by the ogf $F(z) = (q+pz)^n$. Note that $F’(z)\mid_{z=1} = np (q+pz)^{n-1}\mid_{z=1}=np$ and $F’‘(z)\mid_{z=1} = n(n-1)p^2 (q+pz)^{n-2}\mid_{z=1} = n(n-1) p^2$

- $P(X = x) = [z^x] F(z) = p^x q^{n-x} \binom{n}{x}$

- $E(X) = F’(z) \mid_{z=1} = np$

- $\text{Var}(X) = F’‘(z) + F’(z) - F’(z)^2 \mid _{z=1} = n(n-1)p^2 + np - n^2p^2 = npq$

Geometric Distribution

The geometric distribution is the number of steps a procedure has to be repeated until a success, if the probability of each success is $p$.

We have $P(X = x) = p q^{x-1}$, so it is described the ogf $F(z) = \frac{pz}{1-qz}$. Note that $F’(z) \mid_{z=1} = \frac{p}{(1-qz)^2} \mid_{z=1} = \frac{1}{p}$ and $F’‘(z)\mid_{z=1} = \frac{2pq}{(1-qz)^3} \mid_{z=1} = \frac{2q}{p^2}$.

$P(X > n) = q^n$. Combinatorically, it is the probability that the first $n$ tries are failures. Alternatively, $P(X > n) = 1 - [z^n] \frac{F(z)}{1-z} = 1 - [z^n] \frac{pz}{(1-z)(1-qz)} = 1- [z^{n-1}](\frac{1}{1-z}-\frac{q}{1-qz}) = 1 - (1 - q^n) = q^n$

$E(X) = \frac{1}{p}$ as we can setup the equation $E(X) = p \cdot (1) + q \cdot (1+E(X))$. Alternatively, $E(X) = F’(z)\mid_{z=1} = \frac{1}{p}$.

$\text{Var}(X) = F’‘(z) + F’(z) - F’(z)^2 \mid _{z=1} = \frac{2q}{p^2} + \frac{1}{p} - \frac{1}{p^2} = \frac{q}{p^2}$.

Poisson Distribution

If an event is randomly scattered and has a mean occurrence of $\lambda$ in a time interval, we denote the number of occurrences of the event with the probability distribution $X \sim Po(\lambda)$. Define $Po(\lambda) = \lim\limits_{n \to \infty} B(n,\frac{\lambda}{n})$. Then, we have $P(X=x) = \lim\limits_{n\to \infty} (\frac{\lambda}{n})^x \cdot (1-\frac{\lambda}{n})^{n-x} \cdot \binom{n}{x} = \frac{\lambda^x}{x!} \cdot \lim\limits_{n \to \infty} (1-\frac{\lambda}{n})^n = e^{-\lambda} \cdot \frac{\lambda^x}{x!}$.

Thus, $Po(\lambda)$ is described by the ogf $F(z)=e^{\lambda (z-1)}$. Note that $F’(z) \mid _ {z=1} = \lambda e^{\lambda(z-1)} \mid _ {z=1} = \lambda$ and $F’‘(z)\mid _ {z=1} = \lambda^2 e^{\lambda(z-1)} \mid _ {z=1} = \lambda^2$.

Therefore, as we expect, $E(X) = F’(z)\mid_{z=1} = \lambda$ and $\text{Var}(X) = F’‘(z) + F’(z) - F’(z)^2 \mid _{z=1} = \lambda^2 + \lambda - \lambda^2 = \lambda$.

Additive property of Poisson Distribution: If $X \sim Po(\lambda)$ and $Y \sim Po(\mu)$, then $X+Y \sim Po(\lambda + \mu)$. Proof: $e^{\lambda(z-1)} \cdot e^{\mu(z-1)} = e^{(\lambda+\mu)(z-1)}$

Since the Poisson Distribution is the limit of a Binomial Distribution, we can use the Poisson Distribution with $\lambda = np$ to approximate Binomial distributions with large $n$ ($n > 50$) and small $p$ ($p < 0.1$).

Continuous Random Variables

Let $X$ be a continuous random variable. Let the function $c(x) = P(x \leq X)$ denote the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of $X$.

For $X$ to be a continuous random variable, it has to satisfy:

- $\lim\limits_{x \to -\infty} c(x) = 0$

- $\lim\limits_{x \to \infty} c(x) = 1$

- monotone non-decreasing

- right continuous ($x$ is right continuous if for every $\epsilon>0$, there exists a $\delta>0$ such that for all $x \leq y < x +\delta$, it satisfies $\lvert c(x)-c(y) \rvert < \epsilon$, i.e. $\lim\limits_{y \to x^+} c(y) = c(x)$).

We can define the probability density function (pdf) as $p(x) = \frac{d}{dx} c(x)$, $p$ may not be defined for all real numbers as there may be discontinuities in $c$. To simplify things, we will not handle random variables that are both discrete and continuous, so that we shall assume $c$ is continuous.

From here we shall assume $c$ is continuous to assume that $p$ is defined for all real numbers.

Under those assumptions, we have:

- $P(a < X < b) = c(b)-c(a)$

- $P(X = c) = 0$

- $\int_{-\infty}^\infty p(x) = 1$

- $\int_{-\infty}^\infty x \cdot p(x) = E(X)$

- $\int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x) \cdot p(x) = E(f(X))$

Common Continuous Distributions

Uniform Distribution

If $X$ is uniformly distributed on $[a,b]$, then $p(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{b-a}, & a \leq x \leq b \ 0, & \text{otherwise}\end{cases}$.

- $E(X) = \int_{a}^{b} \frac{x}{b-a} \, dx = \frac{b^2-a^2}{2(b-a)} = \frac{a+b}{2}$

- $E(X^2) = \int_{a}^{b} \frac{x^2}{b-a} \, dx = \frac{b^3-a^3}{3(b-a)} = \frac{a^2+ab+b^2}{3}$

- $\text{Var}(X) = E(X^2) - E(X)^2 = \frac{a^2+ab+b^2}{3} - (\frac{a+b}{2})^2 = \frac{(a-b)^2}{12}$

Exponential Distribution

Suppose that an event happens randomly with mean occurrence $\lambda$ in $1$ unit of time. Then $X$ is gives the distribution of the first occurrence of the event.

From the Poisson Distribution, we know that $P(X \leq x) = 1- P_{Po(\lambda t)}(X=0) = 1- e^{-\lambda x}$.

Therefore, $p(x) = \frac{d}{dx} 1- e^{-\lambda t} = \lambda e^{-\lambda x}$, for $x \leq 0$.

- $E(X) = \int_{0}^{\infty} x \lambda e^{-\lambda x} \, dx = [-x e^{-\lambda x} ]_{0}^{\infty} + \int _{0}^{\infty} e^{-\lambda x} \, dx = \frac{1}{\lambda}$

- $E(X) = \int_{0}^{\infty} x^2 \lambda e^{-\lambda x} \, dx = [-x^2 e^{-\lambda x} ]_{0}^{\infty} + \int _{0}^{\infty} 2xe^{-\lambda x} \, dx = \frac{2}{\lambda^2}$

- $\text{Var}(X) = E(X^2) - E(X)^2 = \frac{2}{\lambda^2} - (\frac{1}{\lambda})^2= \frac{1}{\lambda^2}$

Normal Distribution

The standard normal distribution has the $p(x) = e^{-x^2}$, without scaling.

$\int_{- \infty}^{\infty} e^{-x^2} \, dx = \sqrt{\int_{- \infty}^{\infty} e^{-x^2} \, dx \cdot \int_{- \infty}^{\infty} e^{-y^2} \, dy} = \sqrt{\iint_{\mathbb{R}^2} e^{-(x^2+y^2)} \, dx \,dy} = \sqrt{\int_0^\infty \int_0^\tau r e^{-r^2} \,d\theta \, dr} = \sqrt{\tau \int_0^\infty r e^{-r^2} \, dr} = \frac{\sqrt \tau}{\sqrt 2}$.

We can also compute the variance as $\int _ {-\infty}^{\infty} x^2 \cdot e^{-x^2} \, dx = ([-\frac{x}{2} \cdot e^{-x^2}] _ {-\infty}^{\infty} + \int _ {-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{1}{2} \cdot e^{-x^2} \, dx) = \frac{\sqrt \tau}{2 \sqrt 2}$.

Therefore, the pdf of a standard normal distribution has the form $\frac{1}{\sqrt{\tau}} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}$. It has $\mu=0$ and $\sigma=1$.

Denote the normal distribution as $X \sim N(\mu, \sigma)$, which is defined as $\frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{\tau}} e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}$.

Note that analytically solving for $\int e^{-x^2} \, dx$ is very hard, people used to use precomputed tables of the cdf of the standard normal distribution. Now, we just use GC.

The standard normal distribution look like that. There is the empirical rule, also known as the 68-95-99 rule, which states the probability of being having $1 \sigma$, $2\sigma$ and $3\sigma$ deviation respectively.

The $z$-score of normal distribution is the value of a normal distribution $N(\mu,\sigma)$ when it is transformed into the standard normal distribution $N(0,1)$. Clearly, $z = \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma}$.

Let $X \sim N(\mu_X, \sigma_X)$ and $Y \sim N(\mu_Y, \sigma_Y)$, then $X+Y \sim N(\mu_X + \mu_Y, \sqrt{\sigma_X^2 + \sigma_Y^2})$.

It suffices to show that the convolution of 2 standard normal distributions is also normal and we can hand wave the rest.

To do this, notice that the graph $f(x,y) = p_X(x) \cdot p_Y(y)$ is rotationally symmetric. $p_{X+Y}(z)$ is defined as the area under the line $x+y=z$ in $f(x,y)$. Since $f(x,y)$ is rotationally symmetric, it is the area under the line $y = \frac{z}{\sqrt{2}}$ by rotating it using the rotation matrix $R(\frac{\tau}{8}) =\begin{pmatrix} \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} & -\frac{1}{\sqrt 2} \\ \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} & \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} \end{pmatrix}$. The required area is thus $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2} \sqrt \tau} e^{-\frac{z^2}{4}}$, noting that the extra factor of $\frac{1}{\sqrt 2}$ accounts for the fact that the new $y$ value increases by $\sqrt 2$ when the old $y$ value increases by $1$. The pdf of $p_{X+Y}(z) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2} \sqrt \tau} e^{-\frac{z^2}{4}}$ corresponds to $X+Y \sim N(0,\sqrt{2})$.

Central Limit Theorem

Theorem: Let $X_1,X_2,\ldots,X_N$ be random variables drawn from the same distribution. As $N \to \infty$, $X_1 + X_2 + \ldots + X_N$ approaches a normal distribution.

Intuitively, consider the set $S$ of all continuous random distributions with $\mu=0$ and $\sigma=1$. Let $f(X):S \to S$ whose output is the convolution $X+X$ but scaled horizontally and vertically so that it is in $S$. Then, we will believe that the normal distribution is the only attractor of the function. And the shape of $f^n(X)$ would be the shape of convolution of $2^n$ copies of $X$. This can be made rigorous using moment generating functions.

Fundamental Theorem of Enginneering Statistics: Let $X_1,X_2,\ldots,X_N$ be random variables drawn from the same distribution. If $N \geq 30$ (or even relatively small $N$ if $X_i$ is symmetric), then $X_1 + X_2 + \ldots + X_N$ is pretty much a normal distribution.

But for us to know the parameters of the resulting normal distribution we will have to know beforehand the parameters (mean, standard deviation) of the original distribution.

Note: the theorem is not saying that the set ${X_1,X_2,\ldots,X_N}$ is a normal distribution. To see why, let $X$ be the distribution whose value is $0$ or $1$ with $\frac 1 2$ probability.

Corollary: Binomial distribution with large $n$ is approximately normal.

Sample Variance and Mean

Let $x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_n$ be a sample of elements from the distribution $X$. In our calculations, we will allow the sample to contain repeated elements.

We will want to obtain an unbiased estimator for $\mu$ and $\sigma^2$. An unbiased estimator is one whose expected value is equals to the value that it is estimating.

$\bar x$ is clearly an unbiased estimator for $\mu$.

It turns out that the unbiased estimator for $\sigma^2$ is not $\frac{1}{n} \sum(x_i - \bar x)^2$ but is actually $s^2 = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum(x_i - \bar x)^2$. As a sanity check, consider what happens when $n=1$. Another sanity check is to consider the distribution whose value is $0$ or $1$ with $\frac 1 2$ probability with a sample size of $2$.

Anyways, to prove this we will use the lemma $\text{Var}(X) = E(X^2) - E(X)^2$.

Linear Regression

Suppose we have points $(y_i,x_i)$ and we want to find a line such that $y_i = ax_i+b$. Of course, in real life, $(y_i,x_i)$ will not line up perfectly, so we will have to define a cost function for all possible choices of $(a,b)$.

Let $\hat y_i = ax_i+b_i$. The residue is defined as $e_i = y_i - \hat y_i$. We wish to minimize $\sum (y_i-\hat y_i)^2$.

More generally, if we have the equation $Ax=b$, $A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$, $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$, $b \in \mathbb{R}^b$ and we wish to minimize $| Ax-b|^2$, how do we find $x$? Our original problem has $A = \begin{pmatrix} x_1 & 1 \\ x_2 & 1 \\ \vdots \end{pmatrix}$ and $b = \begin{pmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ \vdots\end{pmatrix}$.

We have that $f(x) = \mid Ax - b \mid^2 = (Ax-b)^T(Ax-b) = x^T A^TAx - x^T A^Tb - b^TAx + b^Tb$.

Let $\nabla(f) = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1} \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2} \\ \vdots\end{pmatrix}$.

Then, we find that $\nabla(x^TA^TAX)=2A^TAx$, $\nabla(x^TA^Tb) = \nabla(b^TAx) = A^Tb$ and $\nabla(b^Tb)=0$.

Since this is a optimization problem, we want to find $\nabla(f) = 2A^TAx - 2A^Tb =0$.

This simplifies into $A^TA x = A^Tb$.

For our specific case, we have $A^TA = \begin{pmatrix} \sum x_i^2 & \sum x_i \\ \sum x_i & \sum 1 \end{pmatrix}$, $x=\begin{pmatrix} a \\b \end{pmatrix}$ and $A^Tb = \begin{pmatrix} \sum x_i y_i \\ \sum y_i \end{pmatrix}$.

We obtain $a \sum x_i^2 + b \sum x_i = \sum x_iy_i$ and $a \sum x_i + b \sum 1 = \sum y_i$.

This simplifies into $a (x_i^2 - \frac{(\sum x_i)^2}{n}) = \sum x_i y_i - \frac{(\sum x_i)(\sum y_i)}{n}$.

Define:

- $\bar x = \frac{\sum x_i}{n}$, the mean of $x$

- $\bar y = \frac{\sum y_i}{n}$, the mean of $y$

- $s^2_x = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum (x_i - \bar x)^2$, the sample variance of $x$

- $s^2_y = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum(y_i - \bar y)^2$, the sample variance of $y$

- $\text{cov}(x,y) = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum (x_i - \bar x) (y_i - \bar y)$, the sample covariance of $x$ and $y$.

- $S_{xx} = \sum(x_i - \bar x)^2 = (n-1) s_x^2 = x_i^2 - \frac{(\sum x_i)^2}{n}$

- $S_{xy} = \sum(x_i - \bar x)(y_i - \bar y) = (n-1) \text{cov}(x,y) = \sum x_i y_i - \frac{(\sum x_i)(\sum y_i)}{n}$

Therefore, we have $a = \frac{S_{xy}}{S_{xx}}$.

We define $r$ to be Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient as $\frac{\text{cov}(x,y)}{s_xs_y}$, which can be thought about as normalizing $\text{cov}(x,y)$ into $[-1,1]$ so that $r$ will not change when the data set gets translated or scaled.

The Coefficient of Determination $r^2$ is the fraction of variation in the values of $y$ that is explained by the regression line.

Note that $r \frac{s_y}{s_x} = \frac{\text{cov}(x,y)}{s_x^2} = \frac{(n-1) \text{cov}(x,y)}{(n-1) s_x^2} = \frac{S_{xy}}{S_{xx}} = a$.

Residual Plot

From the residuals $e_i$, we can plot out another graph whose best fit line would be constant. From here, we can study the deviations of the points from the best fit line. Ideally, the deviation of the points will be random. Otherwise, some cases that might happen is:

- curved pattern, so linear regression might not be appropriate.

- fan pattern, $y$ has a larger spread for larger $x$, so the prediction for larger $x$ might not be as accurate.

Transforming to Achieve Linearity

- $y=ab^x$, $\log(y) = \log(a) + x \log(b)$, $\log(y)$ and $x$ are linear

- $y = ax^p$, $\log(y) = \log(a) + p \log(x)$, $\log(y)$ and $\log(x)$ are linear

Appendix

Given an ogf $F(z)$ describing a discrete distribution $X$ where $F(z) = \sum p_i \cdot z^i$.

- $E(X) = (xD) F(z) \mid_{z=1} = F’(z) \mid_{z=1}$

- $\text{Var}(X) = (xD)^2 F(z) - ((xD) F(z))^2 \mid_{z=1} = F’‘(z) + F’(z) - F’(z)^2 \mid _{z=1}$

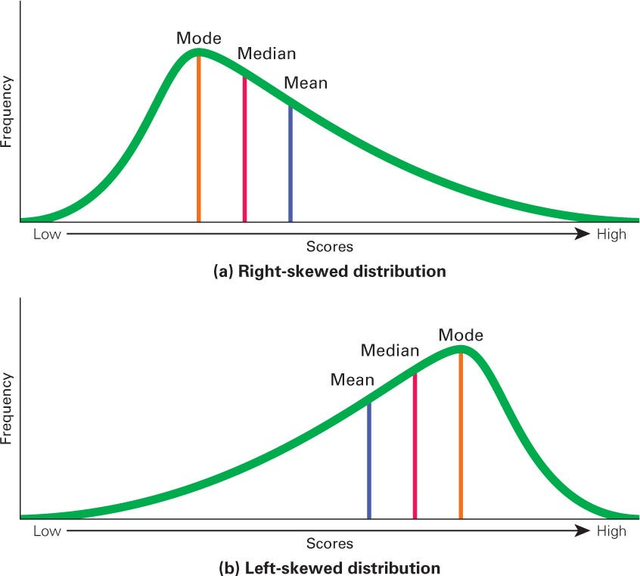

For some weird reason, this is what right and left skew mean. It skews to the side that it tapers off to.