Trigonometry

Trigonometry

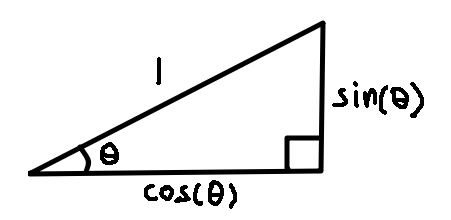

Define $\sin(\theta)$ and $\cos(\theta)$ as the side lengths of the above triangle. Note that these values are defined for all real values of $\theta$, for example with $\frac{\tau}{4}<\theta<\frac{\tau}{2}$, $\sin(\theta)$ is positive but $\cos(\theta)$ is negative.

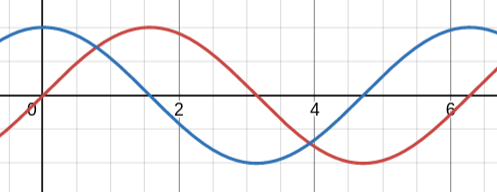

In the above graph, the red line is $\sin$ while the blue line is $\cos$.

Observe that $\sin(\theta) = \cos(\theta - \frac \tau 4)$ and $sin(\theta) = - \sin(\theta + \frac \tau 2)$. Since $\sin$ and $\cos$ are odd and even functions respectively, we have $\sin(\theta) = - \sin(-\theta)$ and $\cos(\theta) = \cos(-\theta)$. Since both functions are $\tau$-periodic, we also have $\sin(\theta) = \sin(\theta + \tau)$ and $\cos(\theta) = \cos(\theta + \tau)$.

By the Pythagorean theorem, we also have $\sin^2 (\theta) + \cos^2 (\theta) = 1$. Note that $\sin^a(\theta)$ is shorthand for $(\sin(\theta))^a$ for positive $a$. $\sin^{-1}(\theta)$ means something else entirely.

We also define the function $\tan(\theta) = \frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)}$. Intuitively, it is the gradient of the line with angle $\theta$. Below is the graph of $\tan$.

Along with those three functions, we also have $\csc(\theta) = \frac{1}{\sin(\theta)}$, $\sec(\theta) = \frac{1}{\cos(\theta)}$ and $\cot(\theta) = \frac{1}{\cot(\theta)}$. They exist for historical reasons because of function tables. We really only need $\sin$ and $\cos$.

Sine Rule

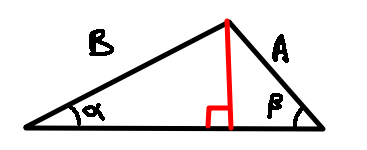

$\frac{\sin(\alpha)}{A} = \frac{\sin(b)}{B}$

Proof:

Drop the red perpendicular line. The length of the perpendicular line is $A \sin(\beta)$ or $B \sin (\alpha)$.

Since we have $A \sin(\beta)=B \sin (\alpha)$, $\frac{\sin(\alpha)}{A} = \frac{\sin(b)}{B}$ follows.

Addition of Trigonometric Functions

$\sin(\alpha+\beta) = \sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta) + \cos(\alpha) \sin(\beta)$

Proof:

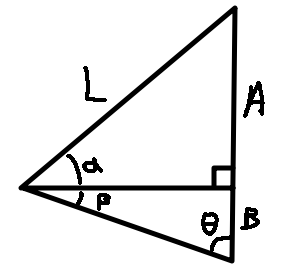

In the above diagram, we have $\frac{A+B}{\sin(\alpha+\beta)} = \frac{L}{\sin(\theta)}$ by sine rule and $A = L \sin(\alpha)$ by the definition of $\sin$.

$\frac{A+B}{\sin(\alpha+\beta)} = \frac{L}{\sin(\theta)} = \frac{A}{\sin(\alpha) \sin(\theta)} = \frac{A}{\sin(\alpha) \sin(\frac \tau4 - \beta)} = \frac{A}{\sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta)}$

Therefore, $(A + B) \cdot (\sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta)) = A \cdot (\sin(\alpha + \beta))$

By symmetry, we also have $(A + B) \cdot (\sin(\beta) \cos(\alpha)) = B \cdot (\sin(\alpha + \beta))$

Adding both equations, we obtain $(A + B) \cdot (\sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta) + \sin(\beta) \cos(\alpha)) = (A+B) \cdot (\sin(\alpha + \beta))$

Therefore, $\sin(\alpha + \beta) = \sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta) + \cos(\alpha) \sin(\beta)$

Corollary: $\sin(\alpha \pm \beta) = \sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta) \pm \cos(\alpha) \sin(\beta)$

Corollary: $\cos(\alpha \pm \beta) = \cos(\alpha) \cos(\beta) \mp \sin(\alpha) \sin(\beta)$

Proof: $\cos(\alpha \pm \beta) = \sin((\alpha + \frac \tau 4) \pm \beta) = \sin(\alpha + \frac \tau 4) \cos(\beta) \pm \cos(\alpha + \frac \tau 4) \sin(\beta) = \cos(\alpha) \cos(\beta) \mp \sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta)$

Corollary: $\sin(2 \theta) = 2 \sin(\theta) \cos(\theta)$ and $\cos(2 \theta) = \cos^2(\theta) - \sin^2(\theta) = 2 \cos^2(\theta) - 1 = 1 - \sin^2(\theta)$

Product to Sum

$2\sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta) = \sin(\alpha + \beta) + \sin(\alpha - \beta)$

$2\cos(\alpha) \sin(\beta) = \sin(\alpha + \beta) - \sin(\alpha - \beta)$

$2\cos(\alpha) \cos(\beta) = \cos(\alpha + \beta) + \cos(\alpha - \beta)$

$2\sin(\alpha) \sin(\beta) = -\cos(\alpha + \beta) + \cos(\alpha - \beta)$

Proofs: expand right side

Sum to Product

If we write $u = \alpha + \beta$ and $v = \alpha-\beta$ above, then $\alpha = \frac{u+v}{2}$ and $\beta = \frac{u-v}{2}$.

Inverse Trigonometric Functions

$\arcsin(\theta)$ is defined as the functional inverse of the function $\sin(\theta)$. However, $\sin$ is not injective as $\sin(0) = \sin(\frac \tau 2) = 0$. Therefore, we restrict the domain of $\sin$ into $\sin:[-\frac \tau 4, \frac \tau 4] \to [-1,1]$, so that we have $\arcsin : [-1,1] \to [-\frac \tau 4, \frac \tau 4]$.

Similarly, we have $\arccos : [-1,1] \to [0, \frac \tau 2]$ and $\arctan : \mathbb{R} \to [-\frac \tau 4, \frac \tau 4]$.

The graphs in green, purple and red are respectively $\arcsin$, $\arccos$ and $\arctan$.

$\csc$, $\sec$ and $\cot$ also have their analogous inverse functions.

Note that most people write $\arcsin$ as $\sin^{-1}$.

Differentiation of Trigonometric Functions

By definition, $\frac{d}{dx} f(x) = \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}$

$\frac{d}{dx} \sin(x) = \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(x+h) - \sin(x)}{h} = \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(x) \cos(h) + \cos(x) \sin(h) - \sin(x)}{h}$

Since $\lim\limits_{h \to 0} \cos(h) = 1$, we have $\frac{d}{dx} \sin(x) = \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(x) \cos(h) + \cos(x) \sin(h) - \sin(x)}{h} = \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(x) (1) + \cos(x) \sin(h) - \sin(x)}{h} = \cos(x) \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(h)}{h}$

Now, we will need to find $\lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(h)}{h}$.

In the above diagram, the area of triangle $ABC$, sector $ABC$ and triangle $ABD$ are $\frac 12 \sin (x)$, $\frac12 x$ and $\frac{1}{2} \tan (x)$ respectively.

So for positive small $x$, we have $\sin (x) < x < \tan (x)$. Dividing all sides by $\sin x$, we obtain $1 < \frac{x}{\sin (x)} < \frac{1}{\cos (x)}$.

Since $\lim\limits_{x \to 0^+} 1 = 1$ and $\lim\limits_{x \to 0^+} \frac{1}{\cos (x)} = 1$, we have $\lim\limits_{x \to 0^+} \frac{x}{\sin (x)} = 1$.

Since $\sin$ is an odd function, $\lim\limits_{x \to 0^-} \frac{x}{\sin (x)} = \lim\limits_{x \to 0^+} \frac{-x}{\sin (-x)} = \lim\limits_{x \to 0^-} \frac{-x}{-\sin (x)}= \lim\limits_{x \to 0^-} \frac{x}{\sin (x)} =1$.

Therefore, $\frac{d}{dx} \sin(x) = \cos(x) \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{\sin(h)}{h} = \cos(x)$.

Corollary: $\frac{d}{dx} \cos(x) = \frac{d}{dx} \sin(x+\frac \tau 4) = \cos(x + \frac \tau 4) = \sin(x + \frac \tau 2) = - \sin(x)$.

The derivative of the other trigonometric functions are easy to derive using derivative rules. In summary:

- $\frac{d}{dx} \sin(x) = \cos(x)$

- $\frac{d}{dx} \cos(x) = - \sin(x)$

- $\frac{d}{dx} \tan(x) = \sec^2(x)$

- $\frac{d}{dx} \csc(x) = - \csc(x) \cot(x)$

- $\frac{d}{dx} \sec(x) = \sec(x) \tan(x)$

- $\frac{d}{dx} \cot(x) = - \csc^2(x)$

Since we have the derivatives of $\sin$ and $\cos$, we can write out its Taylor expansion.

$\sin(x) = \frac{x}{1!} - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!} + \ldots$

$\cos(x) = \frac{1}{0!} - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \frac{x^6}{6!} + \ldots$

Their Taylor expansion is very closely related to the Taylor expansion of $e^x$. Indeed, it is the “simplest” functions that satisfy the differential equation $\frac{d^2}{d^2x} f(x) = -f(x)$.

Consider the function $e^{ix}$ which traces out a circle with radius $1$. We have $e^{ix} = \cos(x) + i \sin(x)$. Since we have $\frac{d^2}{d^x} e^{ix} = - e^{ix} = -\cos(x) - i \sin(x)$, it should be clear why $\sin$ and $\cos$ should satisfy the differential equation $\frac{d^2}{d^2x} f(x) = -f(x)$.

Note that using $e^{ix} = \cos(x) +i \sin(x)$ we can derive the formulas for addition of trigonometric functions.

$\cos(a+b) + i \sin(a+b) = e^{i(a+b)} = e^{ia} \cdot e^{ib} =(\cos(a) + i \sin(a)) \cdot (\cos(b) + i \sin(b)) = (\cos(a) \cos(b) - \sin(a) \sin(b)) + i(\sin(a) \cos(b) + \cos(a) \sin(b))$

Differentiation of Inverse Trigonometric Functions

$1 = \frac{d}{dx} x = \frac{d}{dx} f(f^{-1}(x)) = f’(f^{-1}(x)) \cdot \frac{d}{dx} f^{-1}(x)$

Therefore, $\frac{d}{dx} f^{-1}(x) = \frac{1}{f’(f^{-1}(x))}$.

So, we have $\frac{d}{dx} \arcsin(x) = \frac{1}{\cos(\arcsin(x))}$.

In the above diagram, $\cos(\arcsin(x)) = \cos(\theta) = \sqrt{1-x^2}$

Therefore, $\frac{d}{dx} \arcsin(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}$.

Similarly, $\frac{d}{dx} \arccos(x) = \frac{1}{- \sin(\arccos(x))} = - \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}$

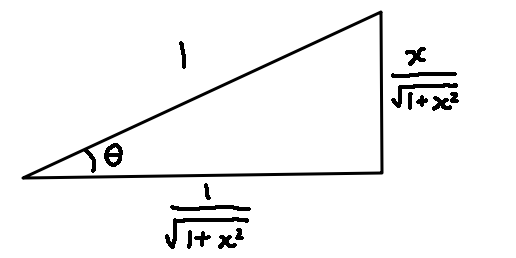

$\frac{d}{dx} \arctan(x) = \cos^2(\arctan(x))$

In the above diagram, $\cos^2(\arctan(x)) = \cos^2(\theta) = \frac{1}{1+x^2}$

Therefore, $\frac{d}{dx} \arctan(x) = \frac{1}{1+x^2}$

Hyperbolic Functions

The hyperbolic functions are the analogue of the trigonometric functions. While the trigonometric functions satisfy $\cos^2 + \sin^2 = 1$ and $\frac{d^2}{d^2x} f(x) = -f(x)$, the hyperbolic functions satisfy $\cosh^2 - \sinh^2 = 1$ and $\frac{d^2}{d^2x} f(x) = f(x)$. They are called hyperbolic functions because $x^2 - y^2 = 1$ is the graph of the unit hyperbola. Apparently they appear as solutions to Laplace equations.

The definition of $\sinh $ and $\cosh$ are $\sinh(x) = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{2}$ and $\cosh(x) = \frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2}$. This is similar to the definitions of $i \cdot \sin(x) = \frac{e^{ix} - e^{-ix}}{2}$ and $\cos(x) = \frac{e^{ix} + e^{-ix}}{2}$.

We can verify that $\cosh^2(x) - \sinh^2(x) = (\frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2})^2 - (\frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{2})^2 = \frac {(e^{2x} + 2 + e^{-2x}) - (e^{2x} -2 - e^{-2x})}{4} = 1$.

Addition of Hyperbolic Functions

$\sinh(x \pm y) = \sinh(x) \cosh(y) \pm \cosh(x) \sinh(y)$

$\cosh(x \pm y) = \cosh(x) \cosh(y) \pm \sinh(x) \sinh(y)$

They should be similar to the normal trigonometric function if one inspects how they are written in terms of $e^{x}$ or $e^{ix}$ respectively. The only difference are in the signs.

Corollary: $\sinh(2x) = 2\sinh(x)\cosh(x)$ and $\cosh(2x) = \cosh^2(x) + \sinh^2(x) = 2\cosh^2(x) - 1 = 1 + 2\sinh^2(x)$

Inverse Hyperbolic Functions

Define $\text{arcsinh}: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$, $\text{arcsinh}: [1,\infty) \to [0,\infty)$ and $\text{arctanh}: [-1,1] \to \mathbb{R}$ as the functional inverses of $\sinh$, $\cosh$ and $\tanh$ respectively.

We can find explicit formulas for these three functions.

Let $y = \text{arcsinh}(x)$, then $\sinh (y) = x$

$e^y = \sinh (y) + \cosh (y) = \sinh (y) + \sqrt{1 + \sinh^2 (y)} = x+\sqrt{1+x^2}$

$\text{arcsinh}(x) = \ln(x + \sqrt{1+x^2})$

Let $y = \text{arccosh}(x)$, then $\cosh (y) = x$

$e^y = \sinh (y) + \cosh (y) = \sqrt{\cosh^2 (y) -1} + \cosh(y) =\sqrt{x^2-1} + x$

$\text{arcsinh}(x) = \ln(x + \sqrt{x^2-1})$

Let $y = \text{arctanh}(x)$, then $\tanh (y) = x$

$1 - \tanh(y) = 1 - \frac{e^y - e^{-y}}{e^y + e^{-y}} = \frac{-2e^{-y}}{e^y + e^{-y}} = \frac{2}{e^{2y} + 1}$

$e^{2y} = \frac{2}{1-x} - 1 = \frac{1+x}{1-x}$

$\text{arctanh}(x) = \frac{1}{2} \ln(\frac{1+x}{1-x})$

Differentiation of Hyperbolic Functions

$\frac{d}{dx} \sinh(x) = \frac{d}{dx} \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{2} = \frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2} = \cosh(x)$

$\frac{d}{dx} \cosh(x) = \frac{d}{dx} \frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2} = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{2} = \sinh(x)$

$\frac{d}{dx} \tanh(x) = \frac{d}{dx} \frac{\sinh(x)}{\cosh(x)} = \frac{\cosh^2(x)-\sinh^2(x)}{\cosh^2(x)} = \frac{1}{\cosh^2(x)}$

$\frac{d}{dx} \text{arcsinh}(x) = \frac{1}{\sinh’(\text{arcsinh(x)})} = \frac{1}{\cosh(\text{arcsinh(x)})} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2+1}}$, since $\cosh(\theta) = \sqrt{\sinh^2(\theta)+1}$

$\frac{d}{dx} \text{arccosh}(x) = \frac{1}{\cosh’(\text{arccosh(x)})} = \frac{1}{\sinh(\text{arccosh(x)})} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2-1}}$, since $\sinh(\theta) = \sqrt{\cosh^2(\theta)-1}$

$\frac{d}{dx} \text{arctanh}(x) = \frac{1}{\tanh’(\text{arctanh(x)})} = \cosh^2(\text{arctanh(x)})= \frac{1}{1-x^2}$, since $\cosh(\theta) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \tanh^2(\theta)}}$

Universal Trigonometric Substitution

Also known as Weierstrass substitution.

If we are integrating a function $f(\theta)$ that can be written in terms of $\sin(\theta)$ and $\cos(\theta)$, we can just apply the substitution $t = \tan(\frac{\theta}{2})$.

$\frac{d \theta}{d t} = \frac{d}{d t} 2 \arctan(t) = \frac{2}{1+t^2}$

$\sin(\theta) = 2 \sin(\frac \theta 2) \cos(\frac \theta 2) = \frac{2 \frac{\sin(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos(\frac \theta 2)} \frac{\cos(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos(\frac \theta 2)}}{\frac{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)} + \frac{\sin^2(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)}} = \frac{2t}{1+t^2}$

$\cos(\theta) = \cos^2(\frac \theta 2) - \sin^2(\frac \theta 2) = \frac{\frac{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)} - \frac{\sin^2(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)}}{\frac{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)} + \frac{\sin^2(\frac \theta 2)}{\cos^2(\frac \theta 2)}} = \frac{1-t^2}{1+t^2}$

\[\begin{align}\int \frac{1}{5+4\cos \theta} \, d \theta &= \int \frac{\frac{2}{1+t^2}}{5+4 (\frac{1-t^2}{1+t^2})} \, d t, \quad t=\tan(\frac \theta 2) \\ &= \int \frac{2}{5(1+t^2) + 4 (1-t^2)} \, d t \\ &= \int \frac{2}{9 + t^2} \, d t \\ &= \frac{2}{3} \arctan(\frac{t}{3}) \\ &= \frac{2}{3} \arctan(\frac{\tan(\frac \theta 2)}{3})\end{align}\] \[\begin{align}\int \sec^6(\theta) \, d \theta &= \int \frac{1}{(\cos^2(\theta))^3} \, d \theta \\ &= \int \frac{1}{(\frac{\cos(2 \theta)+1}{2})^3} \, d \theta \\ &= \int \frac{\frac{1}{1+t^2}}{(\frac{1}{1+t^2})^3} \, d t, \quad t=\tan(\theta) \\ &= \int 1+2t^2 + t^4 \, d t \\ &= t + \frac{2}{3}t^3 + \frac{1}{5}t^5 \\ &= \tan(\theta) + \frac{2}{3}\tan^3(\theta) + \frac{1}{5}\tan^5(\theta)\end{align}\] \[\begin{align} \int \sec(3 \theta) \sec(\theta) \, d \theta &= \int \frac{2}{\cos(3\theta + \theta) + \cos(3\theta-\theta)} \, d \theta \\ &= \int \frac{2}{\cos(4 \theta) + \cos(2 \theta)} \, d \theta \\ &= \int \frac{2}{1 + \cos(2 \theta) - 2 \sin^2(2 \theta)} \, d \theta \\ &= \int \frac{\frac{2}{1+t^2}}{(\frac{2}{1+t^2}) -2 (\frac{2t}{1+t^2})^2} \, d t, \quad t=\tan(\theta) \\ &= \int\frac{1+t^2}{1-3t^2} \, dt \\ &= \int - \frac{1}{3} + \frac{4}{3} \cdot \frac{1}{1-3t^2} \, dt\\ &= -\frac{1}{3}t + \frac{2}{3 \sqrt 3}\cdot \ln \Bigg \lvert \frac{\sqrt 3 + 3t}{\sqrt 3 - 3t} \Bigg \rvert \\ &= -\frac{1}{3} \tan \theta + \frac{2}{3 \sqrt 3}\cdot \ln \Bigg \lvert \frac{\sqrt 3 + 3\tan \theta}{\sqrt 3 - 3\tan \theta} \Bigg\rvert\end{align}\]