MA5131 Summary 5

Definition of Differential Equation

A differential equation is an equation which involves the derivative of a some function.

A differential equation can be characterized by order and degree.

The order of a differential equation is given by the highest derivative that occurs in it.

- $\frac{dy}{dx}=x$ has order $1$

- $\frac{d^2y}{dx}-3\frac{dy}{dx}=x^4-\frac{3}{x}$ has order $2$

The degree of a differential equation is the degree (or power) of the highest derivative.

- $5(\frac{dy}{dx})^7=x$ has degree $7$

- $\frac{d^2y}{dx}-3(\frac{dy}{dx})^{100}=x^4-\frac{3}{x}$ has degree $1$

Suppose that a differential equation has degree $D$. For some expression that satisfies the equation, it can only satisfy the expression where it is $D$-th differentiable, as the $D$-th derivative has to exists.

For the differential equation $\frac{dy}{dx}=\sigma{(x)}$, where $\sigma$ is the sign function. One of the solution is $\lvert x \rvert$, however this solution is only valid on $\mathbb{R} \setminus {0} = (-\infty,0) \cup (0,\infty)$. As a corollary, it also has to be continuous.

Separable Equations

For a differential equation of the form $a(x) \cdot b(y) \cdot \frac{dy}{dx}=c(x) \cdot d(y)$, it can be solved by rewriting the equation as $\int \frac{a(x)}{c(x)} \, dy = \int \frac{d(y)}{b(y)} \, dx$. However, we have performed division by $c(x)$ and $b(y)$ to have arrived at that step. So, we can only perform such a step if $c(x) \neq 0$ and $b(x) \neq 0 \, \forall \, y \in \mathbb{R}$.

To avoid division by $0$, we usually split the differential equation into cases.

$\frac{dy}{dx}=3y^\frac 23$

Case $1$: $y^\frac 23 \ne 0 \, \forall \, x$

$3 y^\frac 13 = 3x + C$

$y^\frac 13=x+A$, $A=\frac C3$

$y=(x+A)^3$

Since $y^\frac 23 \ne 0$, such a solution only holds for $x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {-A}$.

Case $2$: $y^\frac 23 = 0 \, \forall \, x$

$y=0$ is clearly a solution.

Failure of Separable Equations

However, in the previous example, we realize that we have not actually found all the solution, $y=x^3, x \in \mathbb{R}$ is clearly a solution as $y’=3x^2$. In fact, we can find a even more general form of the solution.

\[y= \begin{cases} (x-a)^3,& \text{if } x \leq a \\\\ 0, & \text{if } a < x <b \\\\ (x-b)^3,& \text{if } b \leq x \end{cases} ,\text{where } a \leq b\]This is because not ($y \ne 0 \, \forall \, x$) is actually ($y=0 \, \exists \, x$). That means the casework in the earlier example is inconclusive. However, it is generally hard to analytically solve such equations if you want to solve for $y=0 \, \exists \, x$.

Furthermore, there are even weirder counterexamples of separable equations failing to find all solution.

Consider the differential equation $\frac{dy}{dx}=2 \sqrt{y} \cos (x)$. Using separable equations, we find that there are $2$ general solution, $y=\sin^2 (x), y \ne 0$ and $y=0$.

However, notice that we can combine these $2$ functions similarly to the example shown above, but the weird part is that we form a solution that swap between both solutions an infinite number of times. More specifically in each range $[k \pi,(k+1)\pi]$, we can choose whether we put $y=\sin^2(x)$ or $y=0$ there.

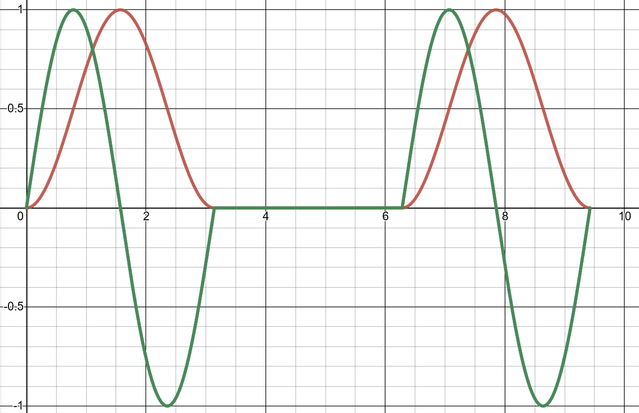

Let us demonstrate that such a solution actually works. Define

\[y=\begin{cases} \sin^2(x),& \text{if } 0 < x < \pi \\ 0, & \text{if } \pi \leq x \leq 2\pi \\ \sin^2(x),& \text{if } 2\pi < x < 3\pi \end{cases}\]It can be verified that such a expression is a solution to the differential equation. A plot of the expression can be found at https://www.desmos.com/calculator/ycdbicyc6q.

Here is a image of the above expression. $y$ is drawn in red and its derivative is drawn in green.

Exponential Growth

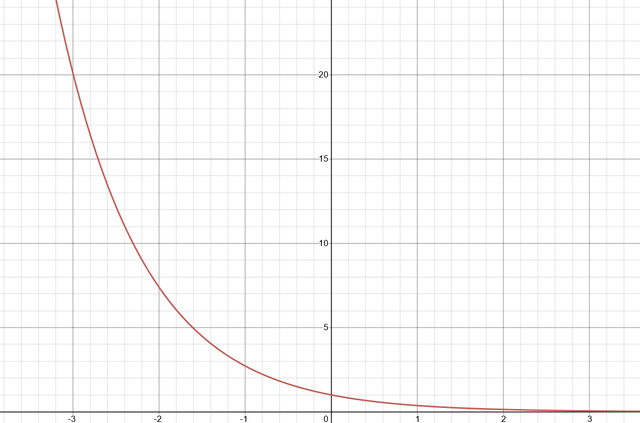

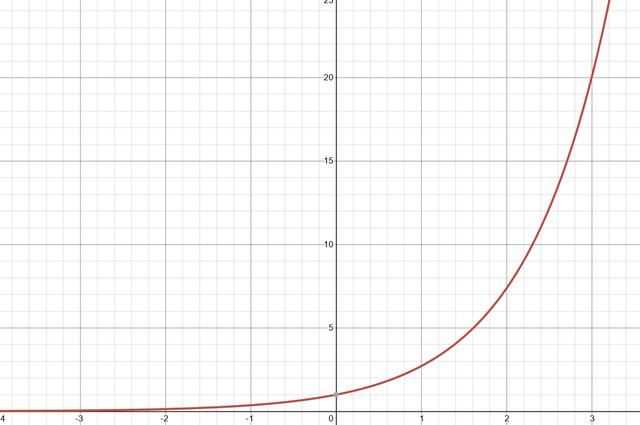

For a differential equation of the form $\frac{dy}{dt}=ky, y(0)=y_0$, the particular solution is given by $y(t)=y_0 e^{kt}$.

$\frac{dy}{dt}=ky$

$\int frac 1y \, dy=\int k \, dt$

$\ln \lvert y \rvert =kt+c$

$y=A e^{kt}$

$y=y_0 e^{kt}$, since $y(0)=y_0$

Slope Fields

For differential equations of the form $\frac{dy}{dx}=F(x,y)$, we can find $F(x,y)$ for some points then plot the slope field.

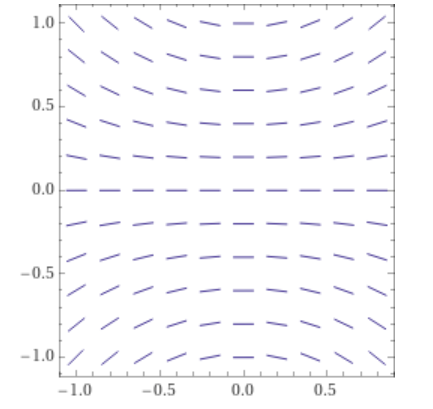

Let’s draw the slope field of $\frac{dy}{dx}=xy$.

First we make a table of the value of the derivative.

| $x=-1$ | $x=0$ | $x=1$ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $y=-1$ | $1$ | $0$ | $-1$ |

| $y=0$ | $0$ | $0$ | $0$ |

| $y=1$ | $-1$ | $0$ | $1$ |

Then we can draw the slope field.

Remember to draw the slope field to scale!

Logistic Growth

For a differential equation of the form $\frac{dy}{dt}=k(L-y)(y), y(0)=y_0$, the particular solution is given by $y(t)=\frac{y_0L}{y_0+(L-y_0)e^{-Lkt}}$.

$\frac{dy}{dt}=k(L-y)(y)$

$\int \frac{1}{(L-y)(y)} \, dy=\int k \, dt$

$\frac{1}{L} \int \frac{1}{L-y} + \frac{1}{y} \, dy=\int k \, dt$

$\ln \lvert \frac{y}{L-y} \rvert =Ae^{-Lkt}$

$y=LAe^{Lkt}-yAe^{Lkt}$

$y(1+Ae^{Lkt})=LAe^{Lkt}$

$y=\frac{LAe^{Lkt}}{1+Ae^{Lkt}}$

$y=\frac{L}{Be^{-Lkt}+1}$

Then, using $y(0)=y_0$, we can find $B$, which is given by $\frac{L-y_0}{y_0}$.

Note that $L$ is defined as the carrying capacity and the position on the slope with the largest growth is the point where $y=\frac{L}{2}$, also since logistic growth is in the form $\frac{dy}{dt}=f(y)$, we can shift our solution parrallel to the x-axis and still get a valid solution.

First Order Differential Equations

An example of a first order differential equation is $\cos(x) \cdot \frac{dy}{dx}+\sin(x) \cdot y=x^3$. Notice that $\cos(x) \cdot \frac{dy}{dx}+\sin(x) \cdot y=\frac{d}{dx}(\sin(x) \cdot y)$.

We can solve this differential equation by writing it as $\frac{d}{dx}(\sin(x) \cdot y)=x^3$. Integrating both sides with respect to $x$, we have $\sin(x) \cdot y=\frac{x^4}{4}+c$. Therefore, the solution to this differential equation is $y=\frac{x^4}{4 \cdot \sin(x)}+\frac{c}{\sin(x)}$.

Generally, we want to solve a differential equation of the form $y+P(x) \cdot \frac{dy}{dx}=Q(x)$. We wish to convert $y+P(x)\cdot \frac{dy}{dx}=\frac{d}{dx}(H(x) y)$. However, it is not always possible to combine the terms directly into a single derivative, this is why we have to introduce a integrating factor.

An integrating factor is a function such that $I(X) \cdot \frac{dy}{dx}+I(X) \cdot P(x) \cdot y=\frac{d}{dx}(I(x)\cdot y)$. Now, we just need to find a function such that $\frac{d}{dx}I(x)=I(x) \cdot P(x)$. Clearly, $I(x)=e^{\int P(x) \, dx}$ is a solution to $I(x)$.

Thus, we can solve first order differential equations.